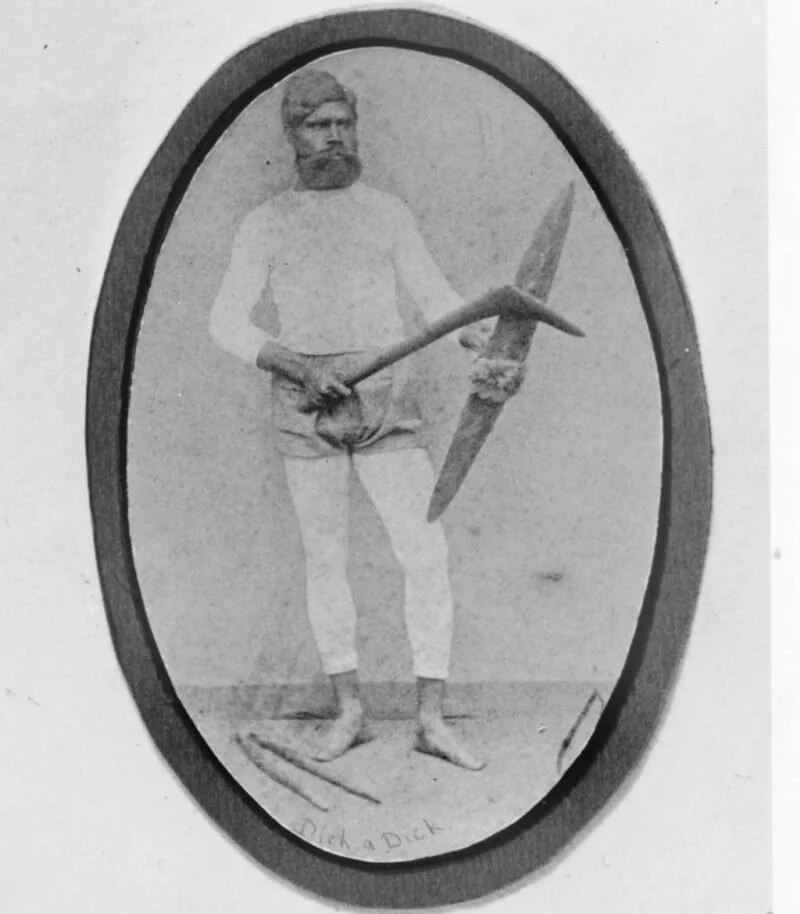

Dick a Dick with his aboriginal weapons

The chart gives some idea about how cramped the itinerary for the tour had been, despite the considerable organisational and persuasive skills of the indefatigable William Hayman. It also shows that the tourists had less than a fortnight to find their land legs after their long voyage, and to acclimatise themselves to the radically different climate. During this section of the tour, the Australian team could win only 1 game and draw 3, losing 6 games. Even so, they had already made a favourable impression on not only the largely pleasure-seeking spectators, but also on the perceptive members of the media and the members of the so called “upper strata” of society. What the above chart does not show, however, is the fact that on several occasions, an exhibition of native Australian athletic skills would follow on the day after the conclusion of a 2-day game, thus further complicating the logistics of the itinerary.

The next block comprised 25 games, and was played mainly in the industrial and mining belt of Yorkshire and Lancashire, with occasional visits to Swansea and Norwich, between the 3rd week of June and the middle of September, as follows:

The Yorkshire segment of the tour would prove to be a sort of turning point for the performance of the visitors and would spark off a series of sterling individual feats. It is said that during the game at York, Mullagh, a fiercely independent and upright individual, had refused to take the field after the Aboriginal players had been excluded from the lunch tent. Could this incident have been the catalyst to the admirable performance of the team as a whole immediately after the York game?

At York, even though Cuzens top score in both innings (32 out of 92 and 42 out of 58), and though Red Cap captured 7 wickets in the home 1st innings, all his victims being bowled, they still lost the game by an innings and 51 runs. Subsequent to this game, however, Cuzens followed up with fifties in consecutive games (87 against Carrow, his highest score of the tour, and 70 against Keighley). On the strength of his 87, Cuzens found a mention in the end of season reports by the Press alongside such illustrious names as WG Grace, Edward Tylecote, and Richard Daft. It should also be mentioned that skipper Lawrence was by now performing miracles with the ball, with 8 five-wicket hauls from 7 games.

The easily visible feature from the above chart is the fact that there were 11 victories in this block of 25 games against 6 losses. Clearly then, the Aboriginals, having spent almost 6 weeks in England by this time, were better acclimatised to the weather conditions by now, and certainly more confident of their cricketing skills. As we have seen above, the team had already lost one important member when King Cole had succumbed to tuberculosis in the 3rd week of June. They were to lose two more members when Sundown and James Crow were sent home in the month of August, presumably because they had been unable to adjust to the English climate and had fallen ill, although there were dark mutterings that alcohol may also have had something to do with it.

Mulvaney and Harcourt report an unusual incident from the drawn game at Bramall Lane. During his innings of 22, Twopenny once drove the ball past mid-on, upon which, “Mr Foster, who was well up, did not offer for some time to go for the ball, and when started it was at a slow pace, the result being that nine was run for the hit amidst vociferous cheering.”

The team was now down to the bare minimum quorum of only 11 fit players including the skipper, and there were still 18 more games to play. The fact that this group of only 11 men could withstand the rigours of the remaining games of the tour between September and October speaks very highly of the determination, fitness, and commitment of the remaining players. They had very nearly lost one more player from the group.

Despite the enthusiasm generated in England by the “novel expedition” of the Aboriginal tour, all was not always smooth sailing for the managerial group of the team. Even though Captain John Williams had gone to great lengths during the voyage to explain to the native cricketers the evils of falling prey to alcohol on their English tour, not everyone was able to resist the charms of the heady brew. Carter reports that “Tiger appears to have got separated from the rest of the team in Sheffield and ended up charged with being drunk and disorderly after assaulting two police officers at two o’clock in the morning. Appearing in court with a bandaged head the following morning he was given a caution and a one pound fine.” It seems that in his inflamed state, Tiger had tried to strangle one of the policemen. He was very fortunate that the Secretary at Bramall Lane had spoken in his favour and had also been gracious enough to pay the fine.

The last 12 games of the tour went as follows:

Although the English weather during this time of the year had not generally been very conducive for cricket, the Aboriginal team had put in a very good performance during this block of games, winning 2 games by an innings, and drawing 8 of them. Two of the games deserve special mention.

In the game against East Hants, Twopenny had the remarkable bowling figures of 10.2-7-9-9 and 12-10-7-6. Of his 15 victims in the game, 12 were bowled, and the only man not dismissed by Twopenny in the home 1st innings was caught by him.

Against the Gentlemen of Hampshire, Twopenny had 9/17 in the 1st innings, bowling unchanged through the innings. He followed up with 3/38 in the 2nd innings, prompting the Hampshire Advertiser to note that: “the bowling of Twopenny was particularly destructive.” His effort against Hampshire netted Twopenny 27 wickets over 2 games at less than 3 runs apiece.

The other game was the one against Reading at the Farborough Cricket Ground, Reading, on 9 and 10 October. After the local team had been dismissed for 32 in 37 overs, with Mullagh capturing 8 wickets for 9 runs, the visitors replied with 284 all out from 154 overs. Opening the batting, Cuzens scored a solid 66, while Mullagh contributed 94, his highest score of the tour. By the end of the tour, it had been established beyond all doubt that Mullagh and Cuzens were their star players, excelling both with the bat and ball and setting a marvellous example to the other members of the squad.

The tourists played a total of 47 games on the tour, winning 14, losing 14, and drawing 19 between May 25, 1868 and Oct 17, 1868. In this 146-day period, there were 20 Sundays when there was no cricket. It is estimated that the visitors spent a total of 99 days out of 126 playing cricket on their 1868 tour of England, a remarkable feat of endurance, given that their original strength had been reduced from 14 to 11 by August, and that they had to play their last 18 games with only 11 players in their camp, including skipper Lawrence. As has been mentioned above, the Aboriginal players were frequently required to take the field on the day following the end of a game to exhibit their native athletic skills, and these days were in addition to the 99 days of cricket.

The figures

Inevitably, a tour of such historical significance generates its own statistical data. Despite the length of the tour and the fact that some of it was played in the latter half of September and the first half of October, not the usual time to play cricket in England, the tour generated enough interest for the media to report incidents from it till the end of the tour. Even Wisden deigned to dignify the cricketing skills of the members of the first ever Australian cricket team to visit England by posting potted scores from the games in their 1869 issue.

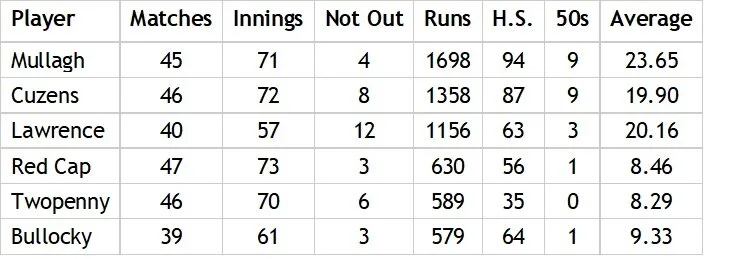

Quoting from Dave Wilson, the principal batting contributors were as follows:

As can be seen, Red Cap played in all the games of the tour, an amazing statistic in itself. Three of the players totalled in excess of 1000 runs on the tour, Mullagh and Cuzens, clearly being the two stars of the team, and scoring 9 fifties each, with Lawrence not far behind. Considering the playing conditions of the day and the nature of the playing surfaces, the top three batsmen in the chart could be rightfully proud of their overall batting averages.

The coaching efforts put in initially by the white settlers in the outlying Australian stations, followed the more intensive drilling by Hayman, Wills, and Lawrence at Edenhope had borne welcome fruit and had won plaudits in the land of the birth of the game.

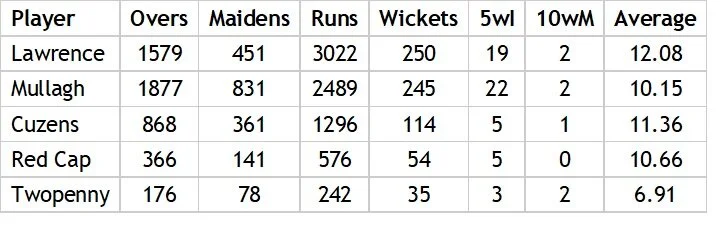

Dave Wilson charts the bowling efforts of the touring Australian Aboriginal team as follows:

Although skipper Lawrence is seen at the top of the list with 250 wickets and 19 five-wicket hauls, the name that really catches the eye is that of Mullagh, with 245 wickets and 22 five-wicket hauls at a very respectable average. The other man with more than 100 wickets on the tour is Cuzens, who proved to be the quickest of the bowlers. When one considers both the batting and bowling performances of the team members in conjunction, it is very clear that the two undoubted all-round native stars of the team were Mullagh and Cuzens, both of whom contributed with both bat and ball right through the tour.

The above bowling chart shows Twopenny bowling only 176 overs, mainly towards the end of the tour. His performances in the games against East Hants and the Gentlemen of Hampshire during the final lap of the tour raises an interesting speculation: given his performances with the ball towards the latter part of the tour, if Twopenny had been given greater opportunities with the ball earlier on during the tour, where would he have finished up on the bowling chart?

Speaking of Mullagh in his book The Fast Men, David Frith says: “a kind of early Sobers, who batted ‘elegantly’, sometimes kept wicket, and with his fastish bowling took 245 wickets at ten runs apiece”. It is said that at some point of the tour, the legendary WG Grace had made the following comment to William Hayman about Mullagh: “with practice Johnny Mullagh would be the finest cricketer in the world.”

Many years later, Charles Lawrence would recall an incident when George Tarrant, one of the leading fast bowlers in England at the time, had offered to give Mullagh some batting practice against quick bowling during the lunch break in one of the games. So engrossed had Mullagh become with the unexpected opportunity to hone his skills with the bat, that he had missed his lunch. Tarrant was to remark that Mullagh was one of the finest batsmen he had ever bowled against.

Sideshows

No discussion about the 1868 Aboriginal tour, however, could ever be complete without mention of the native and athletic activities of the Aboriginal cricketers. There was a memorable exhibition of aboriginal skill with the spear at Nottingham when 3 members faced off against 3 more dressed in their traditional native finery at a distance of about 80 metres. With spears being thrown from both sides, the six Aboriginals were soon “completely hedged in” by a wall of accurately thrown spears, much to the delight of the onlookers. Charley Dumas was renowned for his throwing of the boomerang, Mullagh being another fine exponent of this skill. Peter and Mosquito astonished one and all with their skill with the Aboriginal whip.

Sundown made his remarkable mark with the boomerang and with the traditional throwing stick of the Aboriginal hunters, and so impressed one Lieutenant-General Pitt-Rivers, a Crimean War veteran, that the latter made a detailed study of the art and donated some of the instrument to a London museum.

The first name that springs to the mind in this context of the native athletic skills is that of Dick-a-Dick, referred to at times by the honorific title of King Richard after his astonishing rescue of the three children lost in the bush as mentioned earlier.

Born in the Nhill region of Victoria, Dick-a-Dick was the eldest son of the Wotjobaluk Chief Balrootan. A member of the historic 1868 Australian Aboriginal touring team in England, Dick-a-Dick proved to be an indifferent cricketer but was renowned for his astonishingly quick reflexes and nimbleness of foot. One of the stellar performances displayed by the native Australian players after almost every cricket game was over, goes to the credit of Dick-a-Dick and his trusted leangle (Aboriginal war club) and parrying shield.

The exhibition would consist of Dick-a-Dick standing armed with his shield and his leangle and inviting spectators to throw a cricket or cork ball at him from a distance variously reported as being 10 to 15 paces away while he would dodge the projectiles. He would invite members from the stands to throw the balls at him at a cost of 1 shilling per head. It is said that during the long tour of England, Dick-a-Dick was struck by a ball only twice, first at the conclusion of the 31st game of the tour, at Derby, in the 1st week of September, when he was hit by a Mr Samuel Richardson, later to be captain of Derbyshire, on the left shoulder. On a later occasion, he was struck on a foot. He sometimes also invited several persons to throw the ball at him simultaneously, yet managed to evade the hurled ball miraculously.

Dick-a-Dick was equally proficient in throwing the boomerang and the native spear. Another of his astonishing skills lay in running backwards. Indeed, at the conclusion of the game at Sheffield on the 10th and 11th of August, the Sheffield Telegraph of 13th August had reported his athletic triumphs as follows: won the 100 yards at 10.25 seconds, won the 100 yards backward race, threw a cricket ball the farthest (108 yards, 2 feet, 6 inches), and claimed the 150 yards hurdles race with a timing of 19.5 seconds, despite suffering a fall early in the race.

On other occasions, he was known to have hurled a spear 430 feet and to have won a high jumping contest by clearing 63 inches. It was said at the time in England that only the 20-year old WG Grace, a very promising young cricketer of Gloucestershire, could throw a cricket ball further than Dick-a-Dick’s best throw in England.

This is not to say, however, that Dick-a-Dick was the only one of the native group of cricketers to excel in athletic events. Johnny Cuzens is known to have been the fastest sprinter of the team, and Johnny Mullagh is known to have been a fairly accomplished high jumper in addition to being one of the champion boomerang throwers of the party.

Olly Rickets, writing for Wisden, speaks of a reception arranged for the Australian touring team in Surrey in October/1868, at the official conclusion of the tour. After the speeches on behalf of the hosts had been concluded amidst warm appreciation, Dick-a-Dick had been called upon to reciprocate on behalf of the touring party. Short and to the point, Dick-a-Dick had responded with “We thank you from our hearts.” Legend has it that at the end of the tour, each Aboriginal player had been presented with a cricket bat as a mark of appreciation.

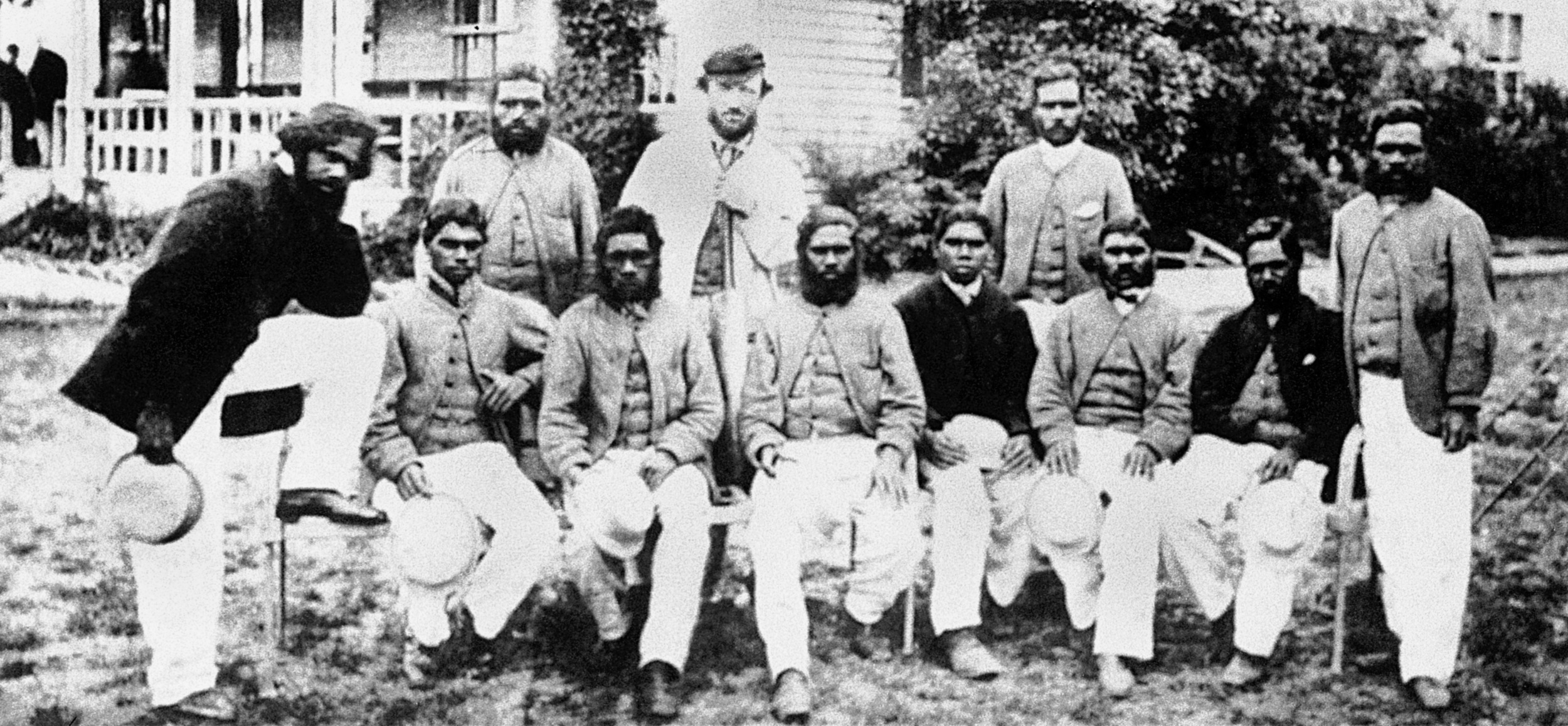

On a different topic, it is said that Dick-a-dick had become enamoured of a white lady during the tour, and it is also rumoured that the lady had been ready to tie the knot with him. Upon hearing of this, however, Lawrence had put a stop to this and had advised Dick-a-Dick to concentrate on his cricket and on his other athletic skills.