Sunil Gavaskar, born on July 10, 1949, was the icon who led India from an also ran to a leader in the world of cricket world with his peerless batsmanship as well as relentless pursuit of proper recognition. Arunabha Sengupta takes a look at the contribution of the man to Indian and world cricket through his playing career and beyond.

Fame, flair and flourish

Late 1983. It was a campaign by Thums Up that went viral among the Indian cricket fans. The fizzy cola took the backseat, the customers lunging for the bottle caps as soon as they were removed by the small metallic openers in street-side shops. The insides of these caps were lined with a small rubbery material. When peeled, they revealed little sketches of the cricketers involved in the then ongoing series between India and West Indies.

Once enough caricatures had been collected to make a team, one needed to send it across to the offices of the beverage company and in return was rewarded with a mini Thums Up bottle replica. That was not all. If one gathered a stipulated number, a more fascinating gift awaited him — a thumb flicker which showed a star cricketer in action. In those days — You Tube was more two decades away — the idea of holding an idol in your hands and having him play a stroke again and again was a rare delight.

The most sought after flickers were those of West Indian captain Clive Lloyd and, of course, the Indian legend Sunil Gavaskar. When one flicked through with the left thumb, Lloyd was seen executing a short-armed pull, and Gavaskar a characteristic straight drive. And when the right thumb flicked through the pages on the other side, both the great cricketers were witnessed drinking from the Thums Up bottles and ending with a satisfied air, raising their thumbs in appreciation and thereby promoting the brand logo.

The magic of Gavaskar was encapsulated even in this little flicker book. His straight drive was a picture of perfection, the bat held absolutely vertical, meeting the ball with the middle, the head down and elbow up, ending with a follow-through out of the coaching manual. Yes, few could fault Clive Lloyd’s stroke as well; but for Gavaskar, not only was his technique perfection itself, the Indians had long believed it to be the platonic ideal of batsmanship.

But the major difference lay in the way the drink was sipped and thumbs were raised. Lloyd made do with a cursory taste, a hint of a smile that could barely be seen under his bushy moustache, and an almost apologetically raised thumb. A cricketer of no mean star appeal, he was not really seasoned in the world of endorsement. However, Gavaskar was another story. He took off the cap with a sweeping gesture, gulped down almost half the bottle, the relish coming alive from the flicked pages, proceeded to emit a soundless satisfied ‘aah’, and finally looked at the camera with a winning smile and raised his thumb with a flourish. This was the man who revolutionised not only the Indian approach towards cricket, but opened up new vistas of making the game into a platform for commercial success. He was the first thorough professional sportsman of India and all the financial fuel on which the game chugs on now was kindled with a spark from this genius.

The many faces of the icon

Yes, his technique was as near perfection as one could get, and his consistency was unnerving — especially in a land of a hit and miss cricketing history such as India. At the same time, he knew that his livelihood had more to do with the perfectly held bat and getting behind the line of the ball. He pioneered not only the art and science of starting the Indian innings, but also the commerce of cricket linked advertising. He knew that the power of his smile, backed by the impeccable straight drive, was as much a selling point as his batting. And when Thums Up asked him to sip, smile and raise his thumb, he did all that and more, he knew it was a part of his profession.

Not only that, he branched into plenty of other areas — discovering channels of entrepreneurship few had thought of before. He wrote articles while playing the game, published his first autobiography when just 27, both in terms of age and Tests — and it went on to become a best seller. He charged appearance money when people were willing to pay for entertaining the team, signed contracts with most of the major manufacturers of sports equipment and even acted in films. He became the first Indian millionaire through the game, and was rich enough to buy a flat in the centre of Bombay.

All this was possible because he had reached dizzy heights with his game which no Indian cricketer had ever aspired to before. And, educated in St Xavier’s, he was articulate, an attribute not too many of his most talented peers enjoyed. He was witty enough to be in the spotlight of the media and advertiser, and he had the fascinatingly macabre virtue of enjoying controversies.

In a capitalist cricketing country, Gavaskar would have been considered a financial genius. However, in this curious land called India, he was often eyed with suspicion.

His batting feats were immortalised in folklore, often tailed by embellishments in an age before satellite television. His popularity soared above anything witnessed in Indian cricket. People waited in queues whenever Gavaskar was sighted going into a shop, just to catch a glimpse in the time honoured darshan concept of India. Right from the day he returned from debut Test series West Indies with 774 runs from four matches, he was viewed as a deity of batsmanship, in the quaint Indian manner of attributing divine powers to their heroes. He did not enjoy the same run of success throughout his career, but that did not matter. According to the Indian, he was godhead of batting and could have no weakness.With time he was considered infallible with the bat.

But, the commercial side of the batting divinity jarred with the Indian dichotomy about money. Indians hanker for wealth, but they do not like heroes to proclaim that they too do so. It attaches too much of a human stigma to someone elevated to mythical levels. And to maintain the flavour of fantasy, the commercial side becomes a projected harmful superpower in the idol, bestowing him a somewhat anti-hero flavour. This was what happened to Gavaskar throughout his career. He was given labels of mercenary. His flirtations with Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket were viewed with circumspection and his so-called lust for money was made a talking point of any discussion surrounding Sunil Gavaskar.

What the Indians prior to globalisation ignored was that by international standards of cricket, Gavaskar was extremely poorly paid for a man of his talents and performance. At the glorious peak of his career, he earned around £35,000 per year. While to the Indians, caught up with their rupee exchange rates, this seemed a huge amount, it was some £5,000 less than what his friend and Somerset colleague Ian Botham earned from his bat contract alone. Let us not even consider the tennis or golf superstars. Gavaskar did his utmost to set things right in terms of the commercial aspects from cricket, and the current generation of cricketers is reaping benefits from efforts kick-started by him. However, to the Indians, he always remained a figure who polarised opinions.

The Indian penchant for praise and abuse

The glorification and the associated dubiousness surrounding Gavaskar’s image was captured in a defining snapshot in the 1983 home series against the West Indies.

At Kanpur, during the first Test, he had a torrid time against Malcolm Marshall. He was dismissed in the first innings by Marshall for a second ball duck. And in the second innings he scored a tormented seven runs, during which his bat had been flung from his hand by a scorcher from Marshall.

In the second Test at Delhi, Gavaskar responded by throwing his enormous quantities of caution — cultivated over a dozen years — firmly to the wind. He had unfurled the hook from his repertoire of strokes after a full decade and had hammered a hundred in 94 balls to catch up with Don Bradman’s 29 and share pole position in the list of Test centurions.

At Ahmedabad in the third Test, Gavaskar sustained his new found aggression and blasted his way to a furious 90 off 120 balls. In the process, he went past Geoff Boycott to emerge and emerged as the highest run-getter in the history of Test cricket. Indians were not used to sportsmen at the very top of the world. As usual divinity was thrust on his shoulders and expectations went spiralling sky high.

Four failures followed, low scores came one after the other in the second innings of Ahmedabad, two outings at Bombay, and finally a first ball duck at Calcutta. The characteristically passionate and excitable Bengali crowd wanted to see Gavaskar go past the Bradman milestone with his 30th hundred. When West Indies lost a few quick wickets, visions of an unlikely victory lent spurs to the anticipation. Lloyd battled it out with a century and took the game away with late order resistance from Andy Roberts. A morose stadium still expected a lot from Gavaskar as he walked out at the fag end of the third day. With the string of poor scores behind him, Gavaskar gambled in trying to hit his way out of trouble. The new image of the supremely patient man which had captured the imagination of the crowd. Four quick boundaries flowed from his bat and were greeted with raucous cheers. And then he chased a wide one to be caught behind. It was a reckless innings that resulted in angry jeers as he walked back. As the team collapsed, Gavaskar was held almost personally responsible for the defeat. The great man was abused at Eden Gardens, not for the last time. Choicest epithets were hurled, and his commitment under skipper Kapil Dev was questioned. There were many voices that clamoured that he was past his best and hanging in there just for the money.

The Delhi hundred was conveniently forgotten, and the lofty praise was soon replaced by guttural abuse in the traditional Indian way. After his return to Bombay Sunil Gavaskar, who took diligent care to open all his fan mail, found a nasty missive in his letter-box. It was a photograph of a chappal (slipper) with an arrow pointing towards him, and alongside lay the inscription, “I present this with due apologies for your performance against the West Indies.” The master was perturbed enough to confide to his mentor Vasu Paranjape that he would make amends.

Gavaskar walked out at No 4 in Madras, the sixth and final Test of the series, with the score reading zero for two. It led to the famous quip by Viv Richards, “Maan, no matter when you come in, the score is always zero!”

Gavaskar batted 644 minutes to remain unbeaten with the then Indian record highest individual score of 236. Although played in a rain-washed match of a dead series with no chance of a result, the innings is still recalled with awe, nostalgic eyes remembering the manner in which he got behind the line of everything Marshall, Michael Holding, Andy Roberts and Winston Davis fired at him. It was a national record that stood for 17 years.

High impact in the face of pressure

This in a nutshell is the story of Sunil Gavaskar — the complex character, often abused, variously misunderstood, mostly but not always uniformly successful, but remembered for high impact innings in the face of pressure.

The ‘high impact innings in the face of pressure’ is indeed a major facet of Gavaskar’s career. Romantics of classical batsmanship turn misty eyed when they recall with understandable fascination the master’s last Test innings — a fighting 96 against the combined spin of Tauseef Ahmed and Iqbal Qasim on a minefield of a wicket at Bangalore in 1987. That day he was out to a dubious decision, and walked back within striking distance of a fantastic win. India lost the match by the slimmest of margins. And it still has the Gavaskar fans reminiscing about the way he continued to play at the very peak of his form till the last day.

It is an excellent glorified conclusion. Only, it is not correct.

Gavaskar did not perform with the same brilliance during the second half of his career. In fact, his batting graph dropped sharply in the 1980s.

He continued to be consistent and among the better batsmen in the 1980s, but was in no way one of the best in the world. In fact, none of the 11 centuries in the latter half of his career came in wins, and a large number of them were inconsequential — the 147 not out in a washed out Test in Georgetown 1982, the 103 not out in a third innings during the last two sessions at Bangalore 1983, 176 in the yawn-inducing draw on a featherbed Kanpur wicket against Sri Lanka in 1986.

In the Indian team itself, Dilip Vengsarkar outscored him by almost 20 runs per innings, Mohammad Azharuddin came in during the last few years of his career and scored at a far superior rate. But, by then, the Gavaskar legend was secure. He was acknowledged as the best batsman of Indian cricket ever, and his performances by then had very little to do with it. Heck, he could even save a Ranji match batting left-handed [1981-82 semifinal against Karnataka]!

He might not have been as consistent as he was in the last few years of his career, but he still ruled public consciousness as the best. But let’s be very clear here: Sunil Gavaskar fully deserved the credit. Unlike some other cricketers later on who were often built solely by the media, Gavaskar had built the aura himself and that too having set the platform with several sterling performances.

A tale of two uncles

None of this might have taken place but for a vigilant uncle at the time of his birth. A mix-up in the hospital had led baby Gavaskar to be exchanged with another infant, son of a fisherman. This uncle, to whom Indian cricket will be forever indebted, noticed that the baby did not have the small hole in the left earlobe that he had seen the previous day. According to his biography Sunny Days: “Providence had helped me to retain my true identity, and, in the process, charted the course of my life. I have often wondered what would have happened it nature had not ‘marked’ me out, and given my ‘guard’ by giving me that small hole on my left earlobe; and if Nan-Kaka had not noticed this abnormality. Perhaps, I would have grown-up to be an obscure fisherman, toiling somewhere along the west coast. And what about the baby who, for a spell, took my place? I do not know if he is interested in cricket, or whether he will ever read this book. I can only hope that, if he does, he will start taking a little more interest in Sunil Gavaskar.”

Then there was another uncle whose influence was no less pronounced.”Nana mama” was as loving and generous an uncle any child could hope for. But his benevolence did not extend to the India sweater he had worn with cherish in the land of his former colonial masters. The proprietary pride came with a sense of achievement. It was to be earned to be savoured — a stinging message he passed on to his young nephew. Madhav Mantri’slesson was worth much, much more than his contributions as a wicketkeeper for India. The seeds that shaped the mind of a cricketing genius probably took roots that day. The message of his uncle became a mantra for Gavaskar in the years that rolled by. At the same time, the tales of the battles his uncle had fought for his country in exotic sounding paces called Old Trafford, The Oval, Headingley, Lord’s were just as exciting to a three-year-old as the epics of Ramayana. Perhaps for him the monsters to be overcome were not Ravana and his legion, but the fiery fast bowlers who had humiliated India in 1952, Fred Trueman, Alec Bedser and the others who had reduced Vijay Hazare’s men to their knees as Mantri had made his few appearances for the country. Perhaps that was what made him steel himself to face the diabolical bowling dished out by the foreign attacks.

Playing straight begins at home

Much in the matriarchal tradition of the Grace family, it was Gavaskar’s mother who gave him practice by bowing to him in their family home. She shed sweat and also blood, as one stroke struck her nose, resulting in profuse bleeding. The sessions went on for hours, sometimes variety introduced into the attack by the recruitment of the services of the houseboy. The game could be indulged in, but the windows could not be broken. The orientation of the house and the furnishings demanded that the batsman play straight, towards the wall at the opposite end. The virtue of charity begins at home, so did the virtue of playing straight.

Gavaskar mentions in his autobiography,Sunny Days, that being admitted into St Xavier’s helped, because the school had a decent team. While the school did indeed have enthusiasm for the sport, their record in the Harris Shield was poor. And Gavaskar, with his pads and bat often looking comical in contrast to his short stature, did not emerge as the star cricketer of the school. Ahead of him were the likes of Feroze Patka and Milind Rege. However, he did receive a lot of encouragement from Father Fritz, who was impressed by his technique and proclaimed that the kid would one day play for India. At 13, he scored his first hundred in the Giles Cup, the Bombay Junior Schools tournament. Within a few months, many inches short of his final height of five feet five inches, he was acknowledged as a formidable opponent. At 16 he played the All-India Schools Competition and notched a compact hundred against the touring London Schoolboys.

It was at this stage that Gavaskar came under the influence of Stan Worthington. The former England player was for years the chief coach of Lancashire, and during the winters came over to India as cricketing missionary. Gavaskar devoured all the knowledge of Worthington’s nine Tests and 33 years of county cricket. The English pro taught Gavaskar the merits of a side-on batting approach, the virtues of playing in the arc between mid-off and mid-on, and why it was dangerous to cut any ball that rose above his wrists. The technique and temperament were fine-tuned under the asbestos sheds of Dadar Union, under the watchful eyes of Vasu Paranjape.

Gavaskar made his rather tepid First-Class debut in the Moin-ud-Dowla for Vazir Sultan Colts in 1966. The Irani Cup debut followed soon. But, the runs began to flow only in 1970, and soon became a deluge. Three hundreds in the space of a few Ranji games soon catapulted him into the Test world, as a wildcard entrant for the West Indies tour of 1970-71.

The dream series

Gavaskar missed the first Test with an attack of whitlow, but romped into the international world in the second. Scores of 65 and 67 not out marked his debut and the epochal first Indian win against the West Indies. The run of scores that followed were Bradmanesque, 116, 64 not out, one, 117 not out, 124 and 220 — the last two innings in the same Test.

Indians had not known such consistency. They were used to heroic spurts of brilliant batting which would suddenly perish in frustrating cameos, with equal probability of being a tale of joy or amounting to nothing. It was the massive spate of run-making during the course of a monumental triumph that made the Indians rejoice. A batting phenomenon had arrived.It is said that Dilip Sardesai, who batted sublimely throughout the tour, was the architect of the win and Gavaskar ensured that the lead was maintained by occupying the crease for ever. But, the sheer weight of runs had their say. The legend of Gavaskar was born.

The lean years and brush with captaincy

Indeed, if we take an unbiased look at Gavaskar’s career, we will find how much this first series had a bearing on his rise as a cricketer. India continued to win, with a maiden triumph in England in the summer of 1971. However, Gavaskar’s contribution was minimal, 144 runs at 24.00 which was a sharp plummet from the lofty 154.80 of his debut series.

A closer analysis reveals that leading up to the New Zealand tour of 1975-76, when Gavaskar led the Indian team for the first time, with Bishan Bedi sitting out due to injury, his performances after the West Indian tour had been less than spectacular. There had been one special hundred on the green wicket of Manchester in 1974 against experts of the conditions — Bob Willis and Chris Old. But, that was the only century after the four in the debut series. In 13 Tests since the Caribbean caper, he had scored a meagre 693 runs at 27.72.

The summer of 1975 had also seen his infamous stonewalling against England in the inaugural World Cup, a painstaking struggle to 36 not out in 60 overs while chasing a huge England total of 334. He looked as much as ease in one-day cricket as MS Subbalakshmi would have been in a rock concert! The 1971-1975 period of Gavaskar is often lost in the folded pages of history that were heard over the wireless sets and seldom seen live. The charisma from the first tour had continued to stride over the airwaves. And, when Bedi was not available, he was the one chosen to lead the team in the first Test in New Zealand.

The greatest period

Gavaskar fitted into the role of captaincy with incredible ease. India won at Auckland and he himself scored 116. Bedi returned for the following Test match and Gavaskar did not lead again for the next few years. Yet, the Auckland Test kick-started an amazing phase for the young man which ran for almost five years — the very best period of his career that established him as one of the very best in the world. We can perhaps say that this was the period that saw Gavaskar peeling off the traditional Indian path of erratic semi-fulfilled promise and paving his way towards greatness with phenomenal consistency.

Two centuries came in his favourite fields of West Indies, with one of them being the launchpad of the miraculous 406-run fourth innings that secured a six wicket victory at Port of Spain. Hundreds were scored almost by force of habit now, as New Zealand and England visited India. And when Australia, depleted severely by the large-scale migrations to Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, hosted the Indian team in 1977-78, a thriller of a series was played out which was finally won by the hosts 3-2. Gavaskar hit centuries in the first three Tests, at Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide, ending with 450 runs in five Tests.

A buoyant India, riding on some excellent showing by the spin attack, ventured to Pakistan — resuming cricketing ties after a decade and a half. Fleet-footed Pakistan batsmen ended the success of the spin story, and virtually the careers of Bedi, Erapalli Prasanna and Bhagwath Chandrasekhar. And the pace of Imran Khan and Sarfraz Nawaz, eminently aided by some dubious umpiring, snuffed out the Indian challenge.

Gavaskar stood alone among the ruins, with 89 at Faisalabad, 97 at Lahore and 111 and 137 at Karachi. Not only did he battle the pace, he also exchanged angry words with umpire Shakoor Rana a decade before Mike Gatting.

Full time captain

Handed the reins of captaincy when the Packer hit rather ordinary West Indians visited India in 1978-79, Gavaskar scored four more hundreds, piling up 732 runs in six Tests. Starting with 205 at Bombay, he scored two hundreds in a match for the third time with 107 and 182 not out at Calcutta, and finished with 120 at Delhi. At the same time, his leadership was questioned because of the measly 1-0 margin of win against a weak Caribbean outfit. His handling of former captain Bishan Bedi raised furious protests from the legendary spinner and his followers. It was sad to see the fallout between two great cricketers, especially after Bedi had named his son Gavasinder after the master batsman.

The leadership was taken away for a while, with the approach by Packer not really endearing Gavaskar to the hearts of the Indian management. Srinivas Venkataraghavan led India to England and Gavaskar responded with 61, 68, 42, 59 and 78 before that epic 221-run marathon at The Oval. He fell two short of equaling the highest fourth innings score in Test history set by George Headley. The degree of difficult in scoring a double hundred in the fourth innings of a Test can be appreciated by the fact that only five batsmen have achieved the feat. Set 438 to win in the last innings, Gavaskar almost pulled off the impossible through one of the best innings ever played in the country. When he was fourth out at 389, the victory was still very much on the cards, but an amateurish scramble for the final few runs ended the challenge nine short with two wickets remaining. Gavaskar piled 542 runs in the four Tests and it was his only successful tour to a country which did not see him quite at his best throughout his career.

And with the same sort of subtlety that is associated with the Indian selectors, it was during the team’s return flight back to India that the pilot announced Gavaskar’s re-appointment as the captain. Venkat also came to know of this news on the aircraft!

There followed a 12-Test home schedule in 1979-80, six apiece against a still weak Australia and a talented Pakistan. Sunil Gavaskar was at his peak. Not only did he continue piling up runs and centuries, 984 runs in all the dozen Tests that winter with three hundreds. The strategies he thought up along with teammates in the hotel rooms bore fruit. Both the opponents were vanquished 2-0. Gavaskar scored 115 against Australia at Delhi and followed it up with 123 at Bombay against the same opponents, and 166 against Pakistan at Madras. The last two were scored in victories, the final Gavaskar centuries in winning causes.

By this time he was the undisputed king of Indian cricket. He ruled the scene, was successful beyond the wildest Indian imagination, as a batsman and captain. Hecould afford to govern the fortune of the nation according to his whims. That is how he stepped down as captain for a couple of Tests for close friend and brother-in-law Gundappa Viswanath to lead in the Calcutta Test against Pakistan and the Jubilee Test of 1980 against England. He resumed his stint at the helm after that. At Calcutta in 1979-80, a four-year-old Rohan Gavaskar trotted into the field during a drinks break. Gavaskar could take those liberties.He dropped out of a scheduled tour to West Indies in 1979-80 and largely due to this the series was cancelled.

Not so sunny days

Things changed as the 1980s rushed in. Gavaskar continued to rule the Indian imagination, on the accepted pedestal of best batsman of the world, but he did not perform as one. It did not quite register in the Indian psyche, but the decline in the scores was very apparent. No one could yet hold a candle to his technique and concentration, but the huge spate of runs dried up.

It started with the Australian tour of 1980-81. With the top Australian players back in action, Dennis Lillee charged in to bowl to Gavaskar. The Indian opener failed. After zero,10, 23, five,10 in five innings, he was desperate for runs. The other time he had faced Lillee had been in the 1971-72 series for the Rest of the World, and he had been less than successful.It was a personal quest for perfection.

In the second innings at Melbourne, he was on his way to redeeming himself. He was batting on 70 when a ball from Lillee struck him on the pad; according to Gavaskar it came off a thick inside edge. Umpire Whitehead’s finger went up, leaving a seething Indian opener wildly gesturing that there was a nick. As he stood there protesting Lillee approached him and told him exactly where his pad had been hit. And as he dragged his unwilling feet away from the crease, there were remarks from some Australian that did not exactly amuse him. Gavaskar lost it. He beckoned his partner Chetan Chauhan and asked him to walk out with him. There could have been a diplomatic crisis. Better senses prevailed in the dressing room, and a reluctantly returning Chauhan was stopped on the ground and made to go back. India won the Test and squared the series through an inspired spell by Kapil Dev, but Gavaskar’s petulance went down as a dark chapter in his story.

India lost the New Zealand leg of the tour and Gavaskar failed quite miserably there as well. The string of low scores were unexpected after a long saga of success, and it played on the mind of the champion batsman. Richard Hadlee pointed out technical deficiencies that had crept in, the guard taken too far towards the leg side, which was inhibiting his ability to get behind the outswinger on the off-stump. Gavaskar absorbed the advice as diligently as ever. He went back to the drawing board and worked patiently on the weakness.

England visited next, in 1981-82, and India won one of the most tedious cricket series ever played. Having won the first Test at Bombay, Gavaskar was content with playing out slow, torturous draws. His batting, never quite express in the seventies, reached new levels of scoreless occupation. In the end, players and spectators both breathed a huge synchronised sigh of relief when the series was over.

The Bombay Test was going to be the last Indian win for three years, and the series victory the last for almost half a decade.The barren 80s had started when India struggled with a limited bowling attack, with the great spinners having departed from the scene and Kapil Dev being the only pacer of quality. Gavaskar’s captaincy, criticised as defensive even when pitted against the limited West Indian side of 1978-79, became extremely safety-oriented.

Additionally, there were increasing problems with teammates. While the ego tussles with Bishan Bedi had become a thing of the past with the latter’s retirement, there were rifts developing with several of the major members of the side. Dilip Vengsarkar, once a protégé, now became distant because of differences.

At the same time, Kapil Dev was capturing the public imagination. The apparent tussle for power and the rift between the two legends of Indian cricket in itself assumed legendary proportions.

India lost in England in 1982, and Gavaskar hardly did anything remarkable except for having his tibia broken by an Ian Botham drive. Besides, some of the selections for the tour, Mumbai men Ghulam Parkar and Suru Nayak in particular, did raise eyebrows and loud whispers of regional bias. It had been a lean run with the bat for 16 Tests and Indians were losing more often than winning. As ever so often happens with a legend in India who crosses 30, whispers about age were starting to make rounds.

Captaincy changes hands

Gavaskar did hit 155 in the inaugural Test against Sri Lanka, but his team could not seal a win against the newcomers. And in Pakistan, he battled the pace and guile of Imran Khan with customary poise, carrying his bat for 127 not out at Faisalabad. But, it was not an unbroken saga of success as had been the previous tour of Pakistan. Mohinder Amarnath overshadowed him with the bat, and India lost dismally by a 3-0 margin.

The captaincy changed hands. The 23-year-old Kapil Dev had turned out to be a cricketer of a kind never witnessed before in India. A pace bowler of world standards and a hard-hitting batsman of immense talent, he had risen in stature and prominence. Now, Gavaskar made his way to West Indies, his land of untold success, under the leadership of this young man from Haryana.

In spite of all his runs against the Caribbean bowlers, it was the very first time Gavaskar was facing the full might of four fearsome pace bowlers bowling together. The only other comparable pace barrage he had faced from the West Indian bowlers had been in the blood bath of Jamaica that had kicked off the West Indian pace machinery in 1976. Gavaskar was not successful in the series. His scores were dismal, 20, zero, one, 32, two, 19, 18 and one. In between there was a 147 not out in a washed out, inconsequential Test match at Georgetown. It was once again MohinderAmarnath who held the centrestage with the bat, a heroic saga of magnificent counter attack with the bat. The 147 notwithstanding, Gavaskar averaged 30 for the series, a big disappointment following his early successes in the land.

This was followed by an atrocious World Cup 1983. India created history with Kapil Dev lifting the trophy with his famous smile,capturing hearts on that epochal June evening. However, Gavaskar managed a mere 59 runs in the tournament at 9.83. By this time, some of the aura that had been built up around him had been tarnished. The Indians, who were convinced about his infallibility — the Bhishma Pitamaha like ability of not getting out unless he wanted to — often equated his poor performances with the lack of motivation under Kapil Dev.

The West Indians arrived for their Test series in India and Gavaskar succeeded in polarising opinions with his fluctuating performances. As mentioned earlier, the 1983 series was a snapshot of the public reaction to the superstar. On one hand the thumb flickers depicting his straight drive and on the other hand, vilification reached a record high. Gavaskar had forever flirted with criticism and controversy, but the reaction of the Calcutta crowd did come as an unpleasant jolt. He redeemed himself with the 236 not out at Madras, but the series was a story of ups and downs.

Gavaskar against pace — busting some myths

It will perhaps be meaningful to indulge in a slight diversion here, as we reach the end of his monumental tussles with West Indies. It is true that Gavaskar scored 2,749 runs against them at 65.45 with 13 hundreds. Added to this we have the impression of that era with four fiery fast bowlers sending down their thunderbolts in tandem.

This has gone on to the creation of the myth of Sunil Gavaskar being the best ever batsman against scorching pace. Even a tentative counter-argument in this context is taken as sacrilege of religious proportions.

Technically he most certainly was the best equipped to take on the fast bowlers. But, unfortunately, his record against express pace is not that flattering.

If we take the best performers during the era West Indies fielded four fast bowlers of quality, we find the Indian opener low down, with just three hundreds and an average that just manages to creep over 40. Great and courageous though he was as a batsman, we tend to overlook that as many as eight of his 13 hundreds against the Windies came against relatively weak attack of 1970-71 and Alvin Kallicharran’s side in1978-79, whose pace power was nowhere near the feared combination that dominated world cricket. During the 1975-76 tour he scored two centuries as well, but they came in separate Tests at Port-of-Spain, on tracks more suited for spin. The last hundred in fact was scored with Clive Lloyd playing the role of the third seamer and 88 overs being shared by spinners Raphick Jumadeen and Albert Padmore. It should also be mentioned that 30% of his runs in West Indies came in a single venue, Queen’s Park Oval.

Gavaskar’s record remained less than excellent against other bowlers of scorching pace as well. He never got on top of John Snow, the bowler who courted infamy by colliding with him mid pitch in 1971. Suspended for a Test after the incident, Snow returned for the Test at The Oval and tore a gold medallion from Gavaskar’s neck with a bouncer. Dennis Lillee also held the upperhand against him in their multiple showdowns. Gavaskar did score hundreds in Australia, five of them across three tours— four visits if we consider the Rest of the World stint in 1971-72. None of these were scored when Lillee bowled. There was Jeff Thomson in 1977-78, a post operation edition, weakened and without support. There were the greenhorn Craig McDermott and rookie Merv Hughes in a transitional Australian side of 1985-86. But, he did not quite score against the best Australian attack. Even then, McDermott struck him in the forearm protector, forcing him to retire hurt.

Of course, we can never be sure how he might have fared against the full strength West Indians if he had played them in 1978-79. Going by the form he was in during that period one could indeed have backed him to succeed immensely.

Gavaskar after retiring hurt, struck on the arm by a McDermott snorter in 1985-86

Where Gavaskar did tackle fast bowlers well was in the subcontinent, where he excelled against Imran Khan’s furious pace, and had a more or less equal exchange against the West Indian greats of 1983. He never flinched against the best of them.But the figures do lend some doubt about the assertion that he was the best against pace in his era.

Gavaskar also did not wear a helmet and this indeed added to the aura of the master. As already mentioned, Indians thrive at bestowing esoteric superhuman powers on their heroes, and Gavaskar’s floppy hat has often been equated with masterly technique that enabled him to avoid the protective gear in days of brutal pace. The truth is somewhat less remarkable. His neck muscles were not strong enough to bear the weight of a helmet over a long innings. As he moved on to cricketing middle-age, Gavaskar adopted a specially made fibreglass skull protector. It emerged only when he took the hat off to mop his brow or acknowledge cheers. But to the fans, it had the effect of keeping his protective gear under the proverbial hat. Never once in his career did the protector come into play. Yet, there are too many who lionise his walking out to face the fast bowling without the gladiatorial gear of his peers.

Captain again

After the rout in the hands of West Indies, the mantle of captaincy was wrenched out of the hand of Kapil Dev and handed back to Gavaskar. And for a brief moment it did seem that the change was bearing fruit. At Wankhede in late 1984, Laxman Sivaramakrishnan spun India to victory in the first Test against England, ending the three year win-less drought. Yet, the euphoria was short-lived. Gavaskar had a miserable series with the bat, scoring 140 runs at 17.50. England drew level in the second Test at Delhi and went ahead in the fourth at Madras, winning the series 2-1.

The series was marked by severe controversy as Kapil Dev was dropped after the Delhi Test after he had come in at a crucial juncture in the second Test and had tried to hit every ball out of the ground. The official version was ‘dropped on disciplinary grounds’. Neither did Kapil take it well nor did the public. And Gavaskar did not help things by letting the Indian innings run on and on during a rain-interrupted Test at Calcutta. The crowd booed and jeered and even pelted rotten fruit and vegetables at the icon and his wife. A pained Gavaskar vowed never to play in the city again.

Two decades later, when Rahul Dravid was shocked to find the Kolkata crowd cheering every run of South Africa after Sourav Ganguly had been dropped from the side, he rationalised saying that he had been given the same status as the great Gavaskar.

Suddenly, the press and public were revelling in the bloodsport of Gavaskar-baiting. Every dismissal was scrutinised, his immense contributions forgotten, voices bayed for his blood and retirement. When Mohammad Azharudddin completed the unprecedented third Test century on the run during his meteoric introduction to international cricket,thousands of observers turned their heads to peer at the Indian cricketers cheering from the pavilion balcony at Kanpur. Gavaskar was not there. Heaps were written about his absence, conjectures floating around about his probable reluctance at sharing the limelight that had so long been his. When Gavaskar declared the second innings at Kanpur in a desperate and rather futile attempt to bowl England out in 80 minutes and 20 mandatory overs on a batting featherbed, the young Azharuddin was unbeaten on 54. There had been a pointed Indian approach to score fast and set England a target in order to make an attempt to square the series. But, even this act of declaration met with curious dissent. Gavaskar supposedly prevented Azharuddin from reaching yet another hundred under the pretension of going for a win. The man, as is the case with most idols of India, could not win whatever he did. Two Tests earlier, his not declaring had aroused vitriol. Now, by doing so he had vilified himself. It led the great man to remark, “Even if it snowing in the Himalayas, it is Gavaskar’s fault.”

One-day wonders

It was one-day wonders that started the path back to somewhere near the top. Gavaskar was retained as captain for the Benson and Hedges World Series Cup in Australia in 1985. After the World Cup win, the one-day game had been revolutionised in India and Gavaskar had woken up to the possibilities of the format. His batting, thoroughly grounded in the five-day version, had been adamantly rooted to the tenets of copybook style. It was now that he slowly came to terms with the ways of fast scoring.

The preparation for the tournament was as near perfect as possible. Gavaskar relinquished the opening slot to Ravi Shastri, who formed an excellent combination with Krishnamachari Srikkanth. Azharuddin, Vengsarkar and Kapil Dev ensured that the captain did not really have to bat more than twice in the tournament. India won emphatically, victorious in all the games. With a magnificent sense of timing, Sunil Gavaskar announced his retirement from captaincy.

The following tournament India played was at Sharjah, a four nation Rothman’s Cup. Kapil Dev led the team and once again they emerged victorious. Gavaskar did not really shine as a batsman, but took four brilliant catches against Pakistan in a low scoring thriller. He was named Man of the Series for his fielding, at the age of 35.

The last years

There was the somewhat ill-advised move of moving down to the middle-order in Sri Lanka in 1985-86. The opening slot had to be filled with men like Lalchand Rajput, and Gavaskar did not really look at ease at number five. A mediocre series ensured that such experiments were discouraged in future. He returned to the top of the order to score two hundreds in Australia, albeit the attack he faced was not the sharpest.

The final tour to England in 1986 was once again a failure, with only one fifty in the six outings with the bat. However, India won the series 2-0 due to some majestic batting by Vengsarkar and combined brilliance of all the bowlers.

Back in India Gavaskar piled on runs. A fantastic 90 in the second innings at Madras during the Tied Test against Australia was followed by 103 at Bombay, the match in which three Mumbaikars, Gavaskar, Shastri and Vengsarkar, all got hundreds. When Sri Lanka came along, the master scored his last Test century, 176 on a placid wicket at Kanpur.

By the time Imran Khan’s Pakistan visited India in 1986-87, it was more or less a foregone conclusion that it would be his last series. With 9,817 runs in 121 Tests, fans waited with bated breath to watch whether the master could go past 10,000 runs.

The series started well, with 91 runs in another of those interest killing flat wickets of Madras. And then came the flabbergasting announcement that Gavaskar would not play the Test match at Eden Gardens.

It was obviously a decision based on the boorish behaviour of the crowd in 1983 and 1984, although the official statement talked of personal reasons. It created a furore of controversy and all the cries of selfishness that had dogged him, but Gavaskar refused to play.

Back in the side in Jaipur, Gavaskar fell first ball, and spent the next few days with his feet up as yet another pathologically boring run feast was played out. He was on 9,942 runs when India met Pakistan at Ahmedabad for the next Test.

10,000

Pioneers in any field have a special place that no else can occupy. That’s the first-mover advantage. The feat of 10,000 runs has been accomplished by several other batsmen since, yetall but the most passionate of cricket fans would struggle to name all of them from memory. Gavaskar, however, would roll off the tip of the tongue.

Sunil Gavaskar by then had long reached a point in his Test career when all that he could do was to pack more muscle to his existing records. He came into the Ahmedabad Test against Imran Khan’s Pakistan needing 58 runs to complete 10,000 runs. Statistics, in that era, was not celebrated and hyped the way it is today. In contrast to the nationwide celebrations and the media blitz today — headlines splashed across page one of the national newspapers and TV channels going on an overdrive — Sunil Gavaskar’s feat of becoming the first cricketer in the 110-years of Test cricket to score 10,000 runs hardly raised a ripple.

Gavaskar reached the milestone with a late cut off Ijaz Faqih for a brace to third man shortly after tea on Day Three. The greying maestro, who said later that the landmark took a lot of pressure of him, raised his bat in delight as set out for the 10,000th run. Even as non-striker Dilip Vengsarkar walked up to Gavaskar, spectators invaded the field to spoil the special moment. Gavaskar would have been livid on any other occasion, but at this moment he was just relived.

As Raju Kulkarni says in SMG, Devendra Prabhudesai’s biography of the Little Master: “I roomed with him during the series against Sri Lanka and Pakistan. Although he was the type who never looked at the scoreboard while batting, and was known to switch off once he was off the field, the fact is that he was edgy as he approached the 10,000 mark. That was the only time I have seen him tense.”

Gavaskar did not last long after the moment, trapped lbw by Imran Khan for 63. During the interview at the end of the day, his disappointment at not reaching a century was writ large on his face.

The Test ended in a draw — the fourth in a row — which meant the two teams the fifth and final Test at Bangalore was decisive for both teams. It was one of the greatest-ever innings by Gavaskar on a minefield of a pitch. He single-handedly tried to win the Test, and with it the series, for India by battling the vicious spin of Tauseef Ahmed and Iqbal Qasim on an underprepared track. Needing 221 for victory, Gavaskar defied the odds, the spinners, the wicket and the pressure the way only he could. Sadly, he was eighth out, still 41 short of victory, when he became a victim of a poor umpiring decision. Gavaskar fell four short of a hundred in his final Test innings and India 17 short of their victory target.

After his 10,000, when fans had cheered him saying “there are many more thousands to come”, Gavaskar had just smiled with a hint of mystery. There were speculations about his retirement, although nothing was specifically announced. There was also a very un-Gavaskar-like bash thrown for journalists at the end of the Bangalore Test But, no announcement was made.

Retirement

It was at Lord’s in the summer of 1987 that Gavaskar finally announced his retirement from international cricket. He did it in style, after 188 runs against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) against Rest of the World in the bicentennial ‘Test’. Marshall, Hadlee, Clive Rice and John Emburey formed a rather useful attack, and Gavaskar batted 404 minutes against them to score his epic last century, the first time he had crossed three figures on that hallowed ground. The announcement was once again fascinatingly timed. There would just be the Reliance World Cup of 1987 that he would participate in before hanging up his boots.

The final tournament of his career once again encapsulated both his genius and the turncoat nature of the fans. In the final group match, Gavaskar hammered an 85-ball hundred, his first in One-Day Internationals. He had come a long way from the stonewalling 36 not out of his early days.

And in the semi-final, he clipped a ball from Phil Defreitas to fine leg for four and was bowled off seventh ball — it was Gavaskar’s final game for India, a match in which a young Sachin Tendulkar ran around the boundary as one of the ball boys.India lost the match at Wankhede. Some last ditch effort by Ravi Shastri was not good enough. Dilip Vengsarkar had sat out due to an upset stomach. In many parts of India it was ridiculously divined as a Bombay clique against captain Kapil Dev. There were demonstrations against Gavaskar and his posters were set on fire. A glorious career was rendered murky in the end by some characteristic irrational hysteria among the masses.

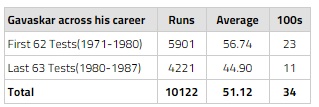

Gavaskar ended with 10,122 runs at 51.12 from 125 Tests with a record 34 hundreds. A safe pair of hands close in, he also created the then Indian record of 108 catches. While mostly stationed in the slips, the one handed take at mid-wicket that dismissed Clive Lloyd in the Ahmedabad Test of 1983 sticks to memory. In ODIs, his record was not flattering, but 3,092 runs at 35.13 was not too bad either for someone who abhorred the format for most of his career.

According to the man himself, it was the stint at Somerset in 1980 that changed his attitude to one-day cricket. However, figures indicate that it was much later that his ODI career flourished, well after India triumphed in the Prudential Cup, and ODIs became far more frequent.

Setting Gavaskar in the context

By the time he ended his career, Gavaskar had been awarded the Padma Bhushan and was without doubt the greatest batsman the country had produced in Test cricket.

Is he the greatest batsman ever to be produced by India? That is definitely not true, especially when contrasted with Sachin Tendulkar’s uniform brilliance across time and countries. Under the microscope there are some gaps that do appear in Gavaskar’s career even though they may seem scandalous when seen through the aura of past glory and the legend that has grown up around him. His record against England remains ordinary in spite of the celebrated 221. He did not really set the grounds on fire in New Zealand either. His post 1980 numbers are perhaps a bit too topsy-turvy.

However, his record needs to be viewed in context of his times. When he entered the scene, Indian cricket was happy with a highest Test match aggregate of 3631 set by Polly Umrigar. It was nowhere near the best in the world arena, but then Indians were happy with their own benchmark. Gavaskar changed all that. He blazed a trail that was unique even by international standards, he set targets aiming for the pinnacle of cricket, not restricted by the parochial low bars of the country. He went beyond being an Indian great, the first Indian cricketer, apart from the brief forays of Vijay Merchant and Vijay Hazare, to etch his name at the top of the honour board of the world scene— and the first to do so over a prolonged period of time.

He was great not only to Indian cricket followers. The world acknowledged him as one. The later cricketers, starting from his younger colleagues Dilip Vengsarkar and Kapil Dev, later Mohammad Azharuddin adjusted their focus to gear for the top. And the next generation of cricketers like Sachin Tendulkar and Rahul Dravid, grew up believing that they could be the best in the world, not just an occasional sterling warrior as the past cricketers had been. And Sunil Gavaskar was the one who made this belief possible.

It was a change of mindset brought along by Gavaskar. And to do that he had to be different.It was this same paradigm shift that led to controversies. There was in Gavaskar a streak which is very similar to find in the other land of great openers — Yorkshire. A hardened sense of achievement and steep standards.

He was acutely aware of his abilities and even more of the lack of regard with which Indian cricket and cricketers were held around the world. It was a burden on him, both for himself and for the sake of the team, to construct a new image of the Indian. And this led him to visualise enemies around him. There were the foreign ones who trivialised teams from India, and then there were the ones in the dressing room, or the ‘jokers’ in the selection panel, who did not quite view his vision in the way he would want them to.

He pursued success with relentless zeal and perfection, at the same time earning for his efforts, and this alienated him from a lot of followers. He was seldom treated with the same warmth and affection as Kapil Dev, or Gundappa Viswanath.

His awareness of the yoke of colonial past made him sensitive to criticism or comments from the English and the Australians, and this also made him outspoken against their views, something that emerges from his opinions even today. It is not beyond Gavaskar to put a racial spin on incidents — sometimes justified and often far-fetched — when circumstances bring the Indians in confrontation with MCC or Cricket Australia. It is perhaps an extension of the same dogged determination which saw him defy the bowlers of those very lands. His relentless purpose was to put Indian cricket and cricketers at par with the world, in terms of stature and financial power. He did pave the way to succeed in his lifetime. It also put him in lasting conflict with many.

A complex character

Much is made of Gavaskar’s feuds with Kapil Dev, Bishan Bedi, Dilip Vengsarkar and others like Dilip Doshi, though he was at fault at times. At the same time, there are several cricketers who have been immensely helped by him, even people weakly linked to cricket through circumstances or not at all. Not too many know of the way Gavaskar courageously stood by the members of the Muslim community during the Mumbai riots of 1993, offering shelter to some. And in spite of rather copious indirect warnings supplied by Bal Thackeray, he did predict Pakistan’s triumph in the 1992 World Cup and crossed the border to be feted regally when the forecast came true.

His perennial conflicts with the occidental powers of cricket were brought to the fore in 1990 when he turned down an invitation to become an honorary member of MCC. Gavaskar had never fallen underthe spell of Lord’s, and unimpressed by the officious and rude manner in which he had been treated by the Lord’s gateman, he took the opportunity to raise his voice.

With India touring England at the same time, and Bishan Bedi being the manager of the Indian side, the incident was escalated dramatically. Bedi walked into the press box of Lord’s to distribute a statement about how shocked he was. He spoke of his own delight of being a MCC member and condemned Gavaskar for dishonouring Indians living in England. How Bedi, a visitor to England, could assume the role of a spokesperson of Indians of the country was an unfathomable mystery, but Gavaskar did not bother to pay any attention to his old foe. MCC renewed their invitation a few years later, and Gavaskar, having made his point, accepted and became a member. He went on to deliver the prestigious Cowdrey Lecture dressed in traditional Indian dress, using the speech to criticise the Australians for on-field sledging. Yes, he was making a point, and it showed. He had not been ready to equate himself with the shabby compromise earmarked for the Indian in the cricket world during his playing days, and was not prepared to do so now.

A few years later, he summarised match referee Mike Procter’s pro-Australian decision on the Sydney Monkey Gate incident as “A white man taking the word of a white man against a brown man.”

It summed up a complex man. Always willing to speak his mind. Not afraid to take up controversial positions. The first modern Indian cricketer to impress himself upon the world, and someone who provokes complex emotions amongst Indians themselves even now.

Gavaskar was awarded the Padma Bhushan during his playing days. Since then he has moved to television commentary, at once popular and controversial as he always was. He has lent his name to the Border-Gavaskar Trophy between India and Australia. And at the same time controversy has continued to dog him, following various remarks in the commentary box, the supposedmanipulations that led son Rohan to get into the Indian ODI team after seasons for Bengal, and many other issues bordering on that fringe of truth and speculation.

Gavaskar also played the role of International Cricket Council (ICC) match referee in one Test and five ODIs. He was the chairman of ICC Cricket Committee until he was forced to choose between commentating and cricket administration. For him it was an easy enough choice. He moved fully into the press box.

Even now, his financial relationship with the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) is severely criticised. Gavaskar continues to evoke strange mix of absolute worship and denigration amongst Indian fans, with the memories of his perfect technique and the evidences of his ‘lust’ for wealth.

Gavaskar’s legacy, however, is difficult to summarise. He took Indian cricket from the smug satisfied lair under the shade of the powerful nations and led the way towards making it a superpower. Yes, there were not too many wins to show for his efforts. Only 23 Tests were won and 34 lost among the 125 he played. But, as he walked out at the top of the innings, the world knew that with him leading the way the team would be no pushover.

His intelligent high attention span helped carry his team on his shoulders with a degree of consistency no Indian batsman before him had exhibited. At the same time, he revamped the commercial structure of cricket, laying the foundations of the modern game.

In multiple ways he remains the Kohinoor of Indian cricket.