Pradip Dhole sketches the life and times of Charles Olivierre, the pioneering cricketer of West Indies

Click here for Part 1

This was the final shape of the squad selected for the England tour: SW Sproston, GC Learmond and WT Burton (Demerara, later to become British Guiana, now Guyana), PJ Cox, W Bowring, PA Goodman and F Hinds (Barbados), LS D'Ade, S Woods and Lebrun Constantine (Trinidad), MM Kerr and GL Livingstone (Jamaica), WH Mignon (Grenada) and CA Ollivierre (St Vincent), with WC Nock (Trinidad) as manager.

Harold (later Sir Harold) Austin, a white cricketer born in Barbados, and one of the more accomplished batsmen of the times, was not available, being in South Africa fighting in the Boer War. Another white player born in Barbados, Hallam Cole, withdrew from the team on personal grounds. Despite his impressive performances against Lord Hawke’s and Arthur Prietley’s teams in 1897, Barbadian fast bowler Archie Cumberbatch was not selected in the party.

The selected squad did not have a specialist wicketkeeper and the ‘keeping duties were shared by Constantine and Learmond. And thereby, as they say, hangs a tale. Constantine and Learmond developed a deep and abiding friendship on the tour, to the extent that Constantine thought it fit to name his son Learie after Learmond.

Ollivierre’s tour

Writing in the 1930s, Caribbean cricket historian CLR James had this to say about Ollivierre: “Up to a few years ago there were experienced West Indian cricketers who believed that Ollivierre was the best batsman the West Indies had ever produced. He was a big powerful man who at school threw 126 yards and cut one-handed for 6. He made most of the strokes with a few of his own, chiefly a glorious lofting drive over extra-cover’s head.”

Dr Adrian Fraser, a social commentator and historian, says that at a Local Cricket Committee meeting in St. Vincent, a decision was taken to raise a “special purse” for Ollivierre, as the batsman left the small island that was his home on 25/May to join the rest of the team at Barbados. According to Dr Fraser, the St. Vincent Handbook had captured the moment; “The jetty was thronged with spectators to wish him ‘bon voyage’. He was presented with a purse, contents of which were contributed by his many friends and well-wishers, also with a congratulatory and encouraging letter. From Barbados, he communicated his thanks with the assurance that nothing on his part would be wanting to make his selection satisfactory.”

The story of the inclusion of Lebrun Constantine, a black plantation foreman, and father of the legendary Baron Learie Constantine, is no less interesting. It seems that he had been passed over initially and that his indignant friends and admirers had then raised the necessary capital to buy his kit and passage money and that he had been escorted to the ship by a group of his well-wishers just prior to the sailing.

The MCC, meanwhile, had met and decided, somewhat arbitrarily, that the standard of play of the tourists was not likely to be of such a high standard as to warrant any of the matches being accorded first-class status. This was somewhat surprising, given that this was to be the first representative team from the West Indies, with players from different colonies that had already been accorded first-class status individually.

While 10 of the 15-member team were white amateur cricketers under Aucher Warner, Tommie Burton, born of a black mother and white father in Barbados, was a coloured professional cricketer, as was Joseph “Float” Woods, born in Barbados, and reputed to be a furiously fast bowler. Delmont Cameron St. Clair “Fitz” Hinds, Lebrun Constantine, and Charles Ollivierre were the coloured amateur cricketers in the group. The members of the touring party met in groups at Barbados, and were entertained at a luncheon at the Ice House by the Barbados Committee, before departing on the RMS Trent on 26 May 1900.

Arriving at Southampton on 6 Jun 1900, the team practised there prior to travelling to London for their first engagement against WG Grace’s London County XI at Crystal Palace from 11 June. Skipper Warner, however, played in only 7 matches on the tour, being laid low by malaria fever, losing all 7 tosses, and placing the team under duress in all the games he played in. Indeed, the early part of the tour was not a happy time for the tourists, given the relatively colder, and more unpredictable, weather and the unaccustomed turf wickets in England, and of course, the higher skill level of the opposition.

It was not an auspicious beginning, London County winning the game by an innings and 198 runs after scoring a forbidding 538 all out. The tourists had to use as many as 8 bowlers (including the wicketkeeper for the match, Constantine). Ollivierre, with figures of 2/24 from his 8 overs, had relatively decent figures. The star performer of the game was Jack Mason of the home team, with a century (126) in his only innings, and figures of 5/50 and 5/43. There is a story, apocryphal perhaps, related by Andy Carter in his work A Flash Outside The Off Stump, of the naturally exuberant Float Woods providing a humorous interlude by looking around the crowd at Crystal Palace and remarking to the Manger of the team, “Mr. Nock, they have a lot of white people in this country.

The visitors lost the first 3 games on the tour by large margins. Well, it is on record that after the formal welcome at London, Aucher Warner had remarked very politely to WG Grace: “We have come to learn, Sir.” Unfortunately, this courteous and deferential remark was grossly misrepresented in a cartoon appearing in the following day’s edition of The Star depicting the familiar bearded figure of WG towering over a group of hideous, weeping pygmies with the caption, “We have come to learn, sah.”

The 21st of June 1900 turned out to be a red-letter for the visiting West Indians when Aucher Warner and his men took the field on the hallowed turf of Lord’s for their game against the Gentlemen of MCC. The home team’s total of 379 all out was built around a century by Ernest Somers-Smith (118). Bowling in tandem, Burton and Woods captured 3 and 4 wickets respectively. The West Indians could muster only 190 all out in the 1st innings, Learmond’s 52 being the high point of the innings. WG Grace took 5 of the wickets. Following on, they put up a score of 295 all out, Lebrun Constantine, batting low down the order at # 9 scoring the first century (113) of the tour, and Burton (64*) giving him admirable support. There was a phase in the 2nd innings when the West Indians were at a precarious 132/8. Constantine and Burton then engineered a partial recovery by adding 162 runs for the 9th wicket in 65 minutes of furious batting, forcing the Gentlemen to bat again. Andrew Stoddart picked up 7/92. The Gentlemen of MCC then won the game by 5 wickets. Even so, Constantine had lit a torch on behalf of the visitors.

The first win of the tour was against the Minor Counties at Northampton from 25/June. Ollivierre (69) had his first fifty of the tour and added 83 runs for the 3rd wicket with Percy Cox (40). Thereafter, Burton (6/55 and 3/11) and Woods (2/57 and 4/31) ensured a victory by 61 runs. The Gloucestershire game at Bristol proved to be a sort of massacre of the innocents when the county side put up 518/7 on the first day of the match, completing the innings at 619 all out from 124 and a half overs. There were 3 centuries, from Harry Wrathall (123), Charlie Townsend (140), and Gilbert “The Croucher” Jessop (157, reportedly scored while 201 team runs were added in a mere hour of batting). According to Plum Warner in My Cricketing Life, “the black men of the team were so amused (at this hitting) that they sat down on the ground and shouted with laughter at the unfortunate bowler's discomfiture!” The West Indians were not up to it and lost the game by an innings and 216 runs, their heaviest defeat till this point.

At the end of the first month of the tour, the West Indians had played 6 games and won only one. It must be remembered that this was a very inexperienced side and they were up against established county sides, often playing to their full potential. As Pelham Warner, a Trinidadian by birth explained, “the team had never played together before, and they were unaccustomed to the strain of continuous three-day cricket.”

The month of July began on a more cheerful note for the visitors with their match against Leicestershire at Grace Road from 2/July ending in a victory by an innings and 87 runs. For a change, the West Indians batted first, and began with a 1st wicket stand of 238 runs in 135 minutes between Plum Warner (113, playing his only match of the tour) and Charles Ollivierre (159, the highest individual score for the visitors on the tour). Bowling unchanged, Woods (5/39) and Burton (4/39) then dismissed the county side for 80 in the 1st innings. Following on, the home side were dismissed for 219.

Two more innings defeats followed, against Nottinghamshire, and, surprisingly, Wiltshire. Against Lancashire in mid-July, the margin of defeat was less, only 57 runs, after good performances by Ollivierre (44 and 60). Johnny Briggs finished the game with a haul of 7/43. The rain-interrupted game against Derbyshire was drawn, the highlight for the tourists being a century (104*) by Percy Goodman, and his 5th wicket stand of 103 with Constantine (62) in just over an hour. For Derbyshire, the enigmatic Bill Storer (who was not keeping wickets in the game) top-scored in both innings with 65 and 57*. Another draw followed in the 2-day game against Staffordshire.

Fortune swung the tourists’ way when they won the next 2 matches. The West Indians won the game against Hampshire by 88 runs despite the heroic efforts of Charles “Buck” Llewellyn, the first “coloured” man to play Test cricket for South Africa. Llewellyn had scores of 93 and 6 and bowling figures of 7/153 and 6/34. For the visitors, Woods bowled well (6/93 and 4/55).

The Surrey game provided the visitors with their best win on the tour. It began with a 1st wicket stand of 208 runs between Ollivierre (94) and Cox (142) to take the total to 328 all out in 86 overs. Burton (2/53 and 4/67) and Woods (7/48 and 5/68) then disposed Surrey for 117 and 177 to gain the team victory by an innings and 34 runs. The next 2 games were drawn, the penultimate match of the tour, against Yorkshire at Bradford being rained off. The last game of the tour, against Norfolk, which the West Indians won by an innings and 16 runs, was a triumph for Burton, who took 8 wickets for 9 runs to dismiss the home side for only 32 runs in 20.4 overs in their 2nd innings.

At the end of the inaugural tour then, the West Indians had played 17 matches in England, winning 5, losing 8, and drawing 4 (the game against Yorkshire being virtually washed off). It was time for reflection on what the tour had achieved for West Indian cricket. This was Plum Warner’s opinion: “I will begin 'right away' as the Americans say, by stating that the tour was a success. Considering that the team had never played together before, that they lost the toss on no fewer than twelve occasions out of the seventeen matches that the programme comprised, I think that the judgment I have given will be endorsed on all sides.”

Wisden’s assessment was more guarded: “A tour which, as an experiment, was extremely interesting and far more successful than might have been expected. As everyone thought at the time, the programme of matches arranged in December was too ambitious, but the defect was easily remedied, the leading counties putting far less than their full strength into the field when the West Indians had to be opposed."

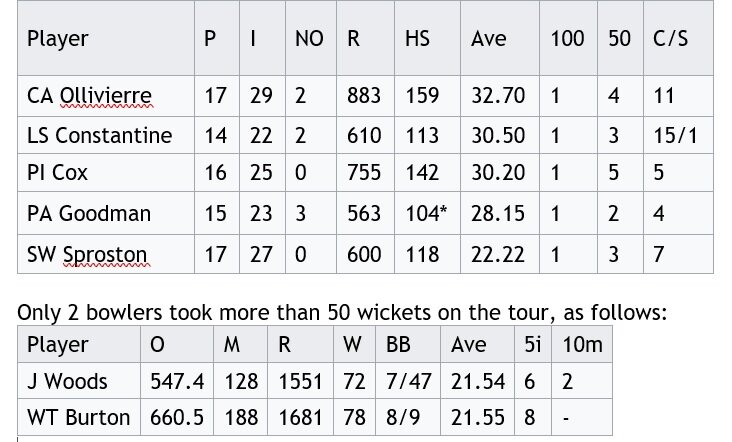

Overall, 5 batsmen aggregated over 500 runs on the tour, with Charles Ollivierre leading the table with a total of 883 runs, as shown below.

Derbyshire

It was reported that a banquet was hosted at the West Indian Club in honour of the West Indian visitors at the conclusion of the tour. The return journey began from Southampton on board the RMS Don on 23 Aug 1900. Not all 15 members of the team were on board the ship on the day, however.

As a direct consequence of his commendable performance on the tour, Derbyshire (third from the bottom in the Championship that year) thought it fit to sign Charles Augustus Ollivierre up to play for the county as an amateur, in a bid to strengthen their doubtful batting. Writing in Derbyshire Life and Countryside, Peter Seddon says that by accepting the offer, Ollivierre “became the first black West Indian to play English county cricket. That broke an important barrier in sporting history, one that had great resonance for the future.” Although his performances in the game against Derbyshire were moderate for a man of his talent (3 and 23*), Ollivierre’s reputation as a fine all-round cricketer had sufficiently impressed the Derbyshire Committee to inspire them to extend the offer to join their ranks. Ollivierre accepted the offer and remained behind in England.

Lord Hawke, the martinet of English cricket, made it clear however, that Ollivierre would be required to fulfil the extant 2-year residency rule before he would be allowed to play Championship cricket as a regular member of the Derbyshire team.

Charles Ollivierre took lodgings with a family in the little market town of Glossop situated in the border areas of the county of Derbyshire. While there, he played some games for the Glossop Cricket Club in the Central Lancashire League, the opportunity coming to him courtesy the sport-loving cotton magnate and captain of Derbyshire, Sam Wood. Ollivierre also turned out in 6 friendly matches for Derbyshire during his time at Glossop.

Ollivierre made his first-class debut for Derbyshire in the match against WG Grace’s London County at the Crystal Palace on 13 May/1901. The debutant acquitted himself well enough, scoring 12 and 54 in a match that was dominated by the batting of George Beldam (125 in 200 minutes, with 11 fours), the man who would later achieve near immortality with his action photograph of Victor Trumper jumping out to drive at The Oval in 1902, and by Tom Fishwick (102 in 150 minutes, with 5 fours), both playing for London County. South African all-rounder Jimmy Sinclair was another star of the game, with 8/32 in Derbyshire’s 1st innings total of 64 all out. Derbyshire went down by an innings and 119 runs in the match.

Ollivierre’s Championship debut was against Essex at home from 24 Jul 1902, a match that Essex won by 120 runs. Ollivierre contributed 20 and 0 in the match. It took some time for the English public to become accustomed to the sight of a black West Indian playing Championship cricket, and the initial reactions were somewhat ambivalent. It was not long, however, before that attitude changed.

Olivierre’s 167 in a first day total of 455/7 in the Championship match against Warwickshire at Derby from 14 Aug/1902 set tongues wagging. The Manchester Guardian was moved to comment: “The hero of the day was C.A Ollivierre, the West Indian, who was batting three hours for a most brilliant and faultless innings of 167 and who thus early proved what a valuable acquisition he is to Derbyshire cricket...his magnificent innings being quite faultless and full of brilliantly executed strokes on either side of the wicket. Three times he hit the ball over the people’s heads, and on twenty-seven other occasions he sent it to the boundary, his other hits being five threes and nine twos.” This was to be his maiden first-class and Championship century. Derbyshire won the game by an innings and 250 runs.

Derbyshire Country Cricket team, 1901 (Back Row L to R): J Humphries, A Warren, W Bestwick, G Curgenven, LG Wright, S Needham (Front Row L to R): W Storer, CA Ollivierre, SM Ashcroft (Captain), S Cadman, HF Wright

Charles Ollivierre’s first class career with Derbyshire spanned the seasons 1901 to 1907 (both included), and he played 110 matches for them, aggregating 4670 runs from his 201 innings (with 4 not outs), with a highest of 229, and an average of 23.70. He had 3 centuries and 24 fifties, and held 109 catches. He also took 10 wickets for them at 41.40.

Play began at Queen’s Park, in the market town of Chesterfield, Derbyshire, under clear skies on 18 Jul 1904 with Essex taking first strike. The first day ended at 524/8, and the one-drop Essex man, Percy Perrin, was still there, batting on 295. Keeping him company was ‘keeper Edward Russell, on 4*. The innings ended the next day at 597 all out, with Perrin undefeated till the end at 343 (scored in 345 minutes, with a record 68 fours). The home supporters may have been experiencing a sinking feeling in the pits of their stomachs at the enormity of the opposition total as the home openers, Levi Wright and Charles Ollivierre, made their way to the wicket on the second day.

A 1st wicket partnership of 191 runs, which ended with the wicket of Wright (68), may have acted as a tonic for the fans. The next wicket fell at 319, and the next at 378, and the home team went in at stumps on the 2nd day with the score reading 446/4, Needham batting on 37 and Curgenven on 17. Earlier in the day, there had been a swashbuckling and muscular innings of 229 by Charles Ollivierre in 225 minutes, with 1 five and 37 fours, full of dazzling shots all around the wicket, executed with gay abandon. The innings ended next day on 548 all out, giving Essex a 1st innings advantage of 49 runs and a psychological boost. The feeling of well-being in the Essex camp was to be short-lived, however

In next to no time, the Essex 2nd innings was over, with only 97 runs on the board and less than 40 overs bowled. Edward Sewell (41) and Johnny Douglas (27) were the only men in double figures. The old Derbyshire war-horse Billy Bestwick (3/34) and right arm fast man Arnold Warren (4/42) had brought Derbyshire right back into the intriguing game. The winning target had been whittled down to only 147 runs in a remarkable turnaround.

Amid mounting excitement around the ground, Derbyshire lost opener Wright (1) with only 11 runs on the board. Was there going to be another twist in the scenario? Birthday boy Ollivierre was still there, however. In the company of the veteran Bill Storer (not keeping wickets in the game), Ollivierre’s strong, dark limbs flashed, despatching the ball to all corners of the field as he played another virtuoso innings on the second successive day to take his team home by 9 wickets.

Ollivierre remained undefeated on 92 and master-minded one of the greatest victories from an almost impossible situation in the history of first-class cricket. The local press reported “one of the greatest ovations ever given to a Derbyshire batsman” as Ollivierre walked back to the pavilion. The triumph was described in Wisden as “the most phenomenal performance ever recorded in first class cricket for never before had a side won a county match after such a high first-innings total had been posted against them.” In his book Summer’s Crown, author Stephen Chalke, quoting a newsfeed, says: “He (Ollivierre) imparts into his late cut an extraordinary amount of energy. Few men affect a more commanding pose at the wicket..”

The game that should have been recognised by posterity as Perrin’s game, went down in history as Ollivierre’s match. Perrin added a forlorn footnote to cricket history by becoming the man with the highest individual score in a defeat. The game generated an amusing anecdote about Ollivierre, very much in keeping with his Caribbean temperament and upbringing. It seems that the celebrations following his double century of the 1st innings had been long and hard. On the last day of the game he had been heard complaining to skipper Maynard Ashcroft, while on the field, of feeling unwell, to the extent that even the church steeple seemed to be falling on him. He had, obviously, never noticed the existence of the famous Crooked Spire of the nearby church before.

On 25 and 26 Jul 1904, in damp and squally weather, English spectators at Derby were witness to an unusual sight, that of a dark-skinned man on each side of a Championship game, as Derbyshire confronted Sussex. When CB Fry declared the Sussex innings closed on the 2nd day at 363/4, Joseph Vine had scored a century (169) and KS Ranjitsinhji, the Indian prince, was batting on 82 glorious, if unorthodox, runs, full of leg-side play, a somewhat alien concept in English cricket at the time. On the other side, Derbyshire had employed 10 bowlers, among them Charles Ollivierre, their import from St. Vincent in the Caribbean. Ollivierre scored only 7 in his only innings as the match had to be abandoned due to the weather.

The 1904 season proved to be very productive for Ollivierre as he scored 1268 runs at an average of 34.27. Spectators in England soon came expect a certain ebullient flair in Olliviere’s approach to batting, something that had not been seen in the county circuit before. Both Ranjitsinhji and he brought, in their own individual ways, a flamboyance and freedom of stroke-play not taught to English schoolboys. Arthur Knight describes Ollivierre as batting with a “certain allusive nuance, suggestive of a far-away glamour which no English player possesses”.

Concluding his essay on the effect of Ranji and Ollivierre on English cricket at the turn of the century, David Mutton says: “Ranji and Ollivierre were pioneers long before the era of mass migration. On the field, they could play as equals, and through their exceptional talent they won the affection of the English public at a time when the vast majority of people had never seen an Indian or a black man. That they achieved this against a background of racism, social Darwinism and plain ignorance is remarkable. On their shoulders sit generations of cricketing migrants who have come to England to grace the game.”

On their shoulders sit generations of cricketing migrants who have come to England to grace the game.”

Charles Ollivierre never returned to the land of his birth and upbringing. He demonstrated his fidelity to his adoptive county by not making himself available to the touring West Indies team of 1906, preferring to honour his commitments to Derbyshire. Ollivierre scored his last first-class century in the game against Leicestershire in June 1906 in his familiar surroundings of Glossop. His 157 in the 1st innings helped him to cross the landmark of 4000 first-class runs and laid the foundation of Derbyshire’s victory by an innings and 50 runs. His association with Derbyshire was long and fruitful, and he always maintained his status as an amateur cricketer.

Later years

In his later years, Charles Ollivierre was afflicted with eye problems which gradually compelled him to retire from first-class cricket at the end of the 1907 season, having registered one duck in each of his last 4 Championship matches. The lure of the cricket green stayed with him till his sixties, however, and he played a more light-hearted genre of club cricket in Yorkshire during his senior years. From the year 1924 through to 1939, up to the outbreak of World War II, he made an annual visit to Holland to coach the young in the nuances of the game that had been his life for as long as he could remember.

There is no record of Charles Ollivierre ever having married. He passed away on 25 Mar, 1949, aged 72 fulfilling years, at Pontefract, West Yorkshire. He was laid to rest at St. Stephen’s Church, Fylingdales, the grave being marked by a simple grave-stone that bears his name but, sadly, makes no mention of his cricketing accomplishments. Even his birthplace is wrongly entered on his memorial.

This rather solitary gravestone on the North Yorkshire coast marks the final resting place of Derbyshire cricketer Charles Augustus Ollivierre (1876-1949).