Ian Johnson, born December 8, 1917, was an off-spinning all-rounder who played for Australia in the 1940s and 1950s and led the country in 17 Tests.Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the life and career of the man who was preferred over Keith Miller as captain of Australia.

More than a Black Sheep

A cricketing nation that has forever believed in handing the reins of leadership to the most charismatic and extraordinary, Australian history has often tended to cast an apologetic look at Ian Johnson. The Victorian all-rounder did lead the country in 17 of his 45 Tests, but was seldom seen as a certainty in the team.

There were players of far more palpable talent, glamour and magnetism, of popular appeal and claims to eternal greatness. There was Neil Harvey, the scintillating southpaw, the backbone of the Australian batting through the post-Bradman decade and more. There was Ray Lindwall of the beautiful run-up, breathtaking speed and buccaneer batsmanship. And finally, there was the dashing, debonair all-rounder Keith Miller, a bonafide great and inspiring skipper of New South Wales. It was Miller who most Australians saw as the worthy candidate to steer this team of extraordinary cricketers. Yet, it was Johnson who became the captain of Australia, leading the more worthy names in the outfit and holding on to his position for a couple of years.

There were other reasons why popular opinion often hauled up his name as a black sheep in the proud history of Australian cricket.

His father William Johnson had been a Test selector before the War and was considered a close friend of Don Bradman. Hence, Bradman’s invisible hand was often detected influencing his selection and later establishing him as the first choice spinner regular of the Invincibles of 1948.

Bradman’s differences with Miller were legendary. Hence, when Johnson was chosen the captain of Australia over the popular all-rounder, perceptions of selector Bradman’s favouritism ran rife. It did not help that Johnson was only intermittently a player of international calibre and obviously several notches below Miller as a cricketer. Even some of his teammates characterised him as Bradman’s pet.

Finally, he was not aided when the team lost the Ashes under his captaincy — twice.

Yet, if we take a look beyond the Miller factor and view the landscape of Australian cricket past the spotlight of the Ashes, we find that there was far more to Johnson than a mere prop of the management. He was a commendable off-break bowler, a reasonably sound lower order batsman and a safe man in the slips. As captain he was hampered by a phase of rebuilding of a great Australian side, and yet ended with more than decent share of successes.

Last, but by no means the least, he was an astute diplomat with well-honed skills at public relations which were really not quite Miller’s forte. Especially in the Caribbean, it was Johnson who was more suited to do the job than Miller, and the Victorian carried out his role wonderfully well.

It is also debatable whether Miller, in charge of the same team, could have delivered a better result. During the two Ashes losses, the side was loaded with several stars over the hill or out of form. There was also a clutch of younger players who were selected in match after match based on promise rather than results.

And as a cricketer, in his own way, Johnson comes across as an inspiring figure. There were several junctures of his career which found himself grappling with the thoughts of quitting. Each time he came out fighting, managed to survive and was, within limits, fairly successful.

Post-War

At the end of the War, Ian Johnson was 27. He had flown the Bristol Beaufighters with the No. 22 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force. By 1944, he had been made a Flight Lieutenant, serving in the South West Pacific. In June 1945, he had already been awarded the Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air for his work as a flight instructor with the No. 11 Elementary Flying Training School at Benalla in rural Victoria.

Two months later, on the day of the Victory over Japan, Johnson was in a slit trench on the South Pacific island of Morotai. It was a Friday which coincided with grog day for the airmen. Johnson drank his whiskey and reflected on his future as a cricketer. “I didn’t have a clue about what would happen to my cricket. I had much more definite ideas as to what I was going to do with that bottle of whiskey,” he recalled later.

Johnson had first played for Victoria in 1935-36. During those initial seasons, he had struggled to establish himself in the side as an off-spinning all-rounder. It was in 1940-41 that he had finally been able to cement his place in the team, and the War had brought all cricketing action to a halt.

However, a few months after the end of the mayhem, he hit a couple of half-centuries in the Sheffield Shield and also captured six for 88 against Queensland at Brisbane. He was picked for the tour of New Zealand. Bradman did not go on that tour but was following the proceedings with a keen eye from home. Perhaps he did have had a hand in the selection of Johnson. One can never be certain.

In New Zealand, Johnson scored a few runs and picked up a few wickets in the side matches, and also played the only Test. With Bill O’Reilly and Ernie Toshack doing most of the damage, and Lindwall and Miller providing the fast bowling thunderbolts as a backup, he was not called upon to bowl.

When Wally Hammond’s England side visited Australia in 1946-47, Johnson produced encouraging performances for Victoria and Western Australia Combined XI. This saw him playing four of the five Ashes Tests.

At Brisbane he was once again not required to bowl but scored 47 in the only innings he played.

He finally got to bowl in the second Test at Sydney. And with his third delivery he struck a major blow by getting Len Hutton caught behind down the leg-side. Using the breeze to excellent effect, he bowled his first spell of11 eight ball overs conceding just three runs for the one wicket. He ended his first bowling innings with figures of six for 42. He picked up two more wickets when England batted again.

The rest of the series was not so successful with the ball, but he did come in at number six at Adelaide and hit a fluent 52, adding 150 with Keith Miller.

When the Indians visited in 1947-48, Johnson was one of the many bowlers who made merry and by the end of the series he had made himself a permanent member of the side to tour England.

As mentioned earlier, Johnson was the first-choice tweaker for Bradman and played in four of the five Tests in the summer of 1948. While this seems curious given his meagre returns of seven wickets at 61.00 apiece and nothing of note with the bat, Johnson did pick up 85 wickets at 18.37 in all First-Class matches on the tour. He also hit 113 not out against Somerset — his first century in top grade cricket.

The happiest tour

Due to his rather poor form in the Tests, it was unclear whether Johnson would be selected for the 1949-50 tour to South Africa. He did bowl well in the domestic season of 1948-49, and also hit 132 not out against Queensland. But, there was still a question mark over his selection. It was a pensive Johnson who drove with his wife Lal — daughter of former Australian Test cricketer Dr Roy Park — to the Essendon Airport in early March 1949 for a trip to Adelaide. He stopped at the air depot on the off-chance that someone there knew the side.

Harry Brerenton of the Victoria Cricket Association was able to confirm his inclusion. Throughout the rest of the journey, a delighted Johnson prattled non-stop about the team composition and the forthcoming tour to the exotic South Africa. He was at first unaware and later confused by the fact that Lal was rather disinterested and dismayed. It was only when he returned from Adelaide that he realised that the day had been March 2, Lal’s birthday, something that had completely slipped his mind.

The South African tour was one of the high points of Johnson’s career. His 66 and three wickets in each innings in Johannesburg set the tone of the series with an innings victory for Australia. Alongside, he was one of the architects behind two other remarkable wins.

Before the Tests, Australia met Transvaal at Ellis Park and were routed for 84 in the first innings and 108 in the second. With the home side requiring just 68 to win in the second innings, the supporters rejoiced. It was the eve of the opening of the Voortrekker Monument at Pretoria commemorating the Afrikaners’ defeat of the Zulus at Blood River in 1838. There was thus a double celebration in the offing. However, Johnson captured six for 22, ending the chase at 50. Australia triumphed by 17 runs. His match haul was nine for 38.

And then there was the strangest of matches in the third Test at Durban. With South Africa at 240 for two in the first innings, a furious downpour rendered the condition well-nigh unplayable. The following morning, wickets fell in a heap — although the tourists dropped several catches to avoid batting on that treacherous track. Finally, the last South African wicket was knocked over at 311. And after a 31 run opening stand, Australia lost all their wickets for 44 additional runs.

Now Johnson produced another lethal spell of five for 34 from 17 eight-ball overs to skittle the hosts for 99 in the second innings. Following this, Neil Harvey hit an unbeaten 151 as Australia overhauled the target of 336 to win by five wickets.

Not only was he successful on field, this was perhaps his happiest tour ever. Captain Lindsay Hassett, Miller, Lindwall, Arthur Morris and Johnson himself formed a merry band of ex-servicemen who rejoiced in their cricket and also stuck together off the field – something that would continue till the mid-1950s. During the South African tour, Hassett and Johnson often performed impromptu duets in public functions, something they would carry on doing even after their playing days.

However, Johnson was not averse from letting his feelings public. During the tour, when asked about the segregation of the society in South Africa, he voiced, “They are living in a fool’s paradise.”

Loss of form

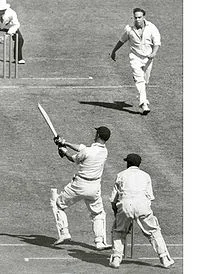

Len Hutton pulls Ian Johnson during the 1950-51 series

The next series was at home against England. The visitors struggled against the mystery spin of Jack Iverson and surrendered from the very beginning. Johnson played all five Tests but did not do much of note except in the third game at Sydney. In that Test, he captured three English wickets in the first innings and scored 77, once again adding 150 with Keith Miller.

In the rest of the series, Johnson’s notable contribution to cricket was at Adelaide — when he walked for a catch at the wicket to grant John Warr at least one wicket in the series. “I got the faintest of faint touches and Godfrey [Evans] went up, half-heartedly. John followed him, but the umpire said not out. Well, I saw John’s shoulders sag, and he looked so crestfallen that on the spur of the moment I nodded to the umpire and walked. It’s the only time I ever did it, I can tell you, but it seemed in keeping with the spirit of the game.”

Johnson’s decline in form continued when the West Indians arrived in 1951-52. He played four Tests and scored just 63 runs and managed to pick up only eight wickets. However, even in this series there was a gesture that went beyond the numbers. Along with wicketkeeper Gil Langley, Johnson opened his home to the tourists and entertained them lavishly. When spinner Alf Valentine told him that he enjoyed the records of ‘Sirravon’, the Victorian searched all over Melbourne in vain for the works of this artist. It later came to light that Valentine was talking about Sarah Vaughan.

By the time the South Africans visited in 1952-53, Johnson’s form was very ordinary. When he was selected ahead of Queenslander Colin McCool for the Brisbane Test, the parochial crowd were not amused. Gil Langley was also one of the villains in the eyes of the spectators, because he had replaced the local stumper Don Tallon. So, when Langley fumbled a stumping chance offered by John Watkins off the bowling of Johnson, the crowd cheered in jubilation.

Johnson was omitted for the rest of the series, and did not manage to make it to the team to tour England in 1953.

Hassett’s pep talk and captaincy

In England, Australia lost the Ashes after 20 years. After the tour Hassett retired, and the Victorian captaincy was handed over to Johnson.

Yet, at the age of 36, Johnson felt that his zest for the game was missing. As Australia had battled for the Ashes in England, he had spent the Australian winter calling football on 3AW with Norman Banks and writing sports columns for the Argus. He seriously contemplated calling it a day and building a new life with Lal and their two boys.

There was a decisive meeting at this juncture, in the home of friend Cecil Kellet during the New Year bash.

As midnight approached, Hassett cornered Johnson. The message was clear: “You’ve had a bad season and I reckon you know why. You’re not getting stuck in…”

Johnson did not agree. He insisted that he was trying. However, Hassett was adamant. “You’re just mucking around. If you’ve got any brains at all, you’ll start taking this game seriously. Because if you do, you’ll end up captaining Australia next year.”

Johnson bristled at the suggestion that he was not putting in his best — because at the back of his mind he knew that it was true. He left the party angrily, but played South Australia that same New Year’s Day. His figures were four for 59 and four for 21. In the next four matches, he picked up 28 wickets at 14.50.

Miller was also scoring runs, taking wickets, and showing some excellent tactical acumen in the Sheffield Shield while leading New South Wales. As the captaincy debate heated up, one Sydney newspaper even wrote: “To choose Johnson over Miller would be tantamount to choosing Edmund Gwenn for the role of Robin Hood when you had Errol Flynn under contract.”

However, Johnson was an alumnus of Wesley College with poise and eloquence of one at home with the high office. He was ahead in the non-cricketing aspects. Miller, a far better cricketer, was after all a Melbourne High School product with a passion for female company, alcohol and the turf. Besides, the support Miller had voiced for Sid Barnes in the recent past — after the batsman had been booked for clowning during a drinks interval — was also held against him.

There were obviously rumours of regional lobbies and bias, but eight days before the 1954-55 Ashes series got underway, Ian Johnson was named captain of Australia.

The beginning could not have been better. At Brisbane, Len Hutton put Australia in and the hosts piled up 601 for eight. Johnson won his first Test match as captain by an innings and 154 runs.

Johnson was out with an injury in the second Test, and as Arthur Morris led the side — Miller was also injured — England struck back with Frank Tyson spewing terror for the batsmen.

By the time Johnson came back for the third Test, the home batsmen had lost heart. Even Harvey had run out of form. Lindwall the bowler had passed beyond his prolonged peak. Ron Archer, Richie Benaud and Alan Davidson were all being played more because of their promise than results. According to Gideon Haigh, “Miller seemed confused whether he wanted to be remembered as a batsman, bowler — or the captain.” Australia surrendered to a 3-1 defeat.

Perhaps no other man in charge of the side could have made any difference, but it did not help Johnson’s cause that he came in to bat at number ten and seemed to bowl only in a supporting role. However, in spite of another attempt by the Sydney faction, Johnson was retained as skipper for the tour of West Indies. He did a fantastic job in the Caribbean.

The triumph in the islands

The 1954-55 tour to West Indies was critical from a lot of non-cricketing angles.

Allan Rae tosses the coin as Ian Johnson calls

The previous year, Len Hutton’s Englishmen had made themselves extremely unpopular by hobnobbing with the whites of the different islands, giving the perception of aloofness from the people of other ethnic origins, disputing umpiring decisions and getting into ugly interactions with the crowd. Johnson started the tour by telling Miller, “Let’s forget the Pommy boys. The West Indies reporters are more important to us.”

His public relation skills, open hand and flair for the mot juste made him a huge hit. He took the team to parties hosted by the local black fans and dignitaries. At Jamaica, Johnson was photographed by Kingston’s Star while improvising a rumba step at the residence of local cricket lover Vernon Sassoo. The caption accompanying the picture announced ‘Calypso Captain’. Miller lent a helping hand as well, marking his guard with the bat handle, drinking Coca-Cola with the crowd and hitting balls into the surrounding palm trees. The team even dealt with the provocative taunts of the crowd with humour. None of the dismissals, however outrageous, was disputed.

The master-stroke was provided by Johnson. While leaving the field through a wave of adoring children, he picked up one of them and exchanged a few laughs with him. It made him a hero in the land. A Jamaican magistrate observed, “Whereas the MCC as a whole gave us the impression that they felt they were stepping down, the Australians seem to have come on a level.”

Australia, powered by the bowling of Lindwall, Miller and Benaud, as well as spectacular batting of almost everyone, won the series 3-0. Johnson scored two fifties, and at Georgetown produced his career-best bowling performance. Bowling into a stiff breeze, he captured seven for 44. Three of his victims were stumped, deceived by the ball dipping in the wind after they had charged out of the crease. A tally of 191 runs at 47.75 and 14 wickets at 29 apiece were excellent returns for the captain.

His only false step during the tour came high in the air, when Miller and he — former RAAF pilots both – took control of a commercial flight from Trinidad and Tobago. The Board was forced to insert a clause into future player contracts, prohibiting them from flying aircrafts.

Yet, not everyone was pleased with him. Some Australian teammates dubbed Johnson ‘Mr Kolynos’ after the toothpaste because of his constant smile. Others called him ‘Myxomatosis’, because he always seemed to bowl only when the rabbits were in.

When Denis Atkinson and Clairmonte Depeiaza were saving the Bridgetown Test with their world record partnership, Johnson got into a heated exchange with Miller who refused to bowl fast and commented, “You couldn’t captain a team of schoolboys.” It was prudent of Johnson to roll up his sleeves and retort, “Step outside then.” The invitation to fight actually helped to tone down the heat.

Also, Bill Johnston did not like it when Johnson came up to him at the nets and said, “Just ’cos you’re one of the old blokes in the side doesn’t mean you don’t have to bloody well put in, you know.” A hurt Johnston responded, “I know I’m one of the old blokes. There’s no need to rub it in.”

However, the tour was a grand success from cricketing and diplomatic points of view. The Australian top brass were thoroughly impressed. Bradman specifically wrote to Prime Minister Robert Menzies recommending an honour for Johnson. The next year, both Miller and Johnson received MBEs.

The Governor of Jamaica, Sir Hugh Foote, also wrote to Menzies, “The good which they have done is beyond praise or calculation.” This remains one of the grand tours of the 1950s, largely forgotten due to poor media coverage.

Lakered and Locked

The summer of 1956 in England was, however, a tour too many for Johnson, as well as for Lindwall and Miller. There was a clear lack of discipline in the side. The senior men did not perform at all. Miller failed to show up for the start of the match against Hampshire. Sid Barnes, writing for the English papers, mocked Johnson as a non-playing captain.

There was success at first, with a win in the second Test at Lord’s. However, Peter May openly communicated to Harvey that it would be “the last pitch you’ll see like that.” The rest of the tracks were tailor made for Jim Laker and Tony Lock. England won the series 2-1, with Laker capturing 19 at Manchester.

Johnson, in his 39th year, captured just six wickets and scored 61 runs in the five Tests. Some of the players later voiced that Miller would have done a much better job of lifting the spirits of the team. Some of Johnson’s actions also became very unpopular. He insisted on every player attending every match even if not in the playing eleven. Hence, for most, there was no break from cricket. Benaud and Harvey were particularly disillusioned.

His tactics too came up for a lot of criticism. His pep-talks were dismissed as unrealistic optimism. When, plagued by turning tracks, he asked Davidson and Archer to bowl spin, Bill O’Reilly described the move as ‘pitiable’.

The exit

On their way back, Australia played a Test in Pakistan and three in India. They lost to Fazal Mahmood’s pace on the matting wicket of Karachi, but in India they won the series 2-0. Johnson scored 73 at Madras, missed the drawn Test at Bombay and ended his career with a wicket in each innings in Calcutta. After returning to Australia he announced his retirement from cricket.

Thus, in his 45th and final Test match, Johnson stumbled to exactly 1000 runs in his career. With 109 wickets, he did achieve the coveted double – a comparably rare feat in his era. His scalps came at 29.19 apiece, while his batting average was a considerably inferior 18.51. A fine fielder in the slips, he held 30 catches.

By the 1950s, cricket had become more of an international sport and the tendency to accord all importance to Ashes was no longer universal. Hence, in spite of Johnson’s two Ashes series defeats, the record of seven wins, five losses and five draws read a creditable captaincy record. His victories in West Indies and India indeed deserved special accolades.

The methods

The art of off-break bowling was rather unusual for an Australian. The pitches of the country encouraged wrist-spin. Johnson’s bowling action was slightly peculiar with a staccato swing of his bowling arm. Most of his success stemmed from flight and intelligent use of the wind with which deliveries floated away from batsmen. E. W. Swanton, observed that Johnson was “probably the slowest bowler to achieve any measure of success in Test cricket.” Ray Robinson described his action writing: “to coax turn from firm Australian pitches he twisted the ball almost hard enough to screw a doorknob off.”

Trevor Bailey however felt that Johnson threw his deliveries. Yet, although Johnson played around the globe, he was never called in his career.

According to Bradman, “Johnson was at his best on dry crumbling wickets—the wet ones made him too slow. It always looked like he could be hit by a fast-footed batsman. That he wasn’t may be put down to his straight ball, which was hard to detect, and often left the striker down the wicket. A most intelligent bowler, always scheming.”

As a batsman, he was prone to be a dour and difficult to dislodge in the lower order. His defence was sound and he could also give the ball a wallop when the situation demanded.

Later days

On his return to Australia after his final tour in November 1956, Johnson was teamed up with fellow Invincible Sam Loxton, alongside tennis star Jack Kramer and sprinting legend Jesse Owens for the GTV-9 commentary panel for the Melbourne Olympics.

In 1957, Johnson was chosen from a group of 44 candidates as secretary of the Melbourne Cricket Club, a position earlier held by Hugh Trumble and Vernon Ransford. Johnson presided over some major redevelopment of the club. He was one of the main organisers of the Centenary Test in 1977.

Johnson also became a salesman — peddling cordials and liquor. Interestingly, Keith Miller did exactly the same.

Johnson was appointed an Officer in the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 1976. In 1982 became a Commander in the Order of the British Empire (CBE). He served as a member of the Victorian state Parole board for 20 years.

Ian Johnson passed away in Melbourne in 1998.